- Design Approaches

- Posted

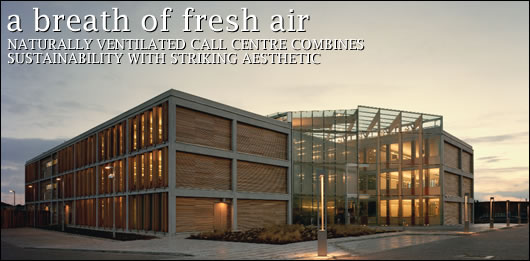

A Breath of Fresh Air

Prestige commercial buildings can place a heavy toll on the environment, typically relying in Ireland on carbon intensive grid electricity to power air conditioning systems throughout the warmer parts of the year and inefficient electric lighting – often all year around. Completed in November 2004, software company SAP’s Galway offices offer a rare opportunity to find out how a natural ventilated and low energy lighting building is working in practice, as John Hearne reveals.Call centres tend to follow the same design principles as battery farms. Entry level staff packed tight together, handling phone calls from far flung time-zones into the early hours of the morning. German software company SAP set out to establish something a little more free range when they commissioned a new 360 person call centre in Galway five years ago.

Merritt Bucholz of Bucholz McEvoy, one of the country’s foremost architects, has been a long-time champion of environmentally aware design. “The brief process was pretty intense because they had this really young group of people who speak five languages, serving time-zones from America to Finland. The problem is if you put really bright people in a box for a long time, they get pretty fed up with their job and they quit. They spend a long time training these guys and they become valuable to them, so the problem was about working with the staff to develop a picture of a building that would support them, not just in their work but also as people, as individuals. Much of the brief came from a process that started with that in mind, and things became defined in terms of, I guess you could call it comfort. There’s lots of detailed points about that, but it really comes down to the issue of comfort.” In a densely occupied office space, comfort is all about ventilation and cooling. Typically, that means air conditioning, but here again, the design team set out to leave convention behind. “I don’t like air conditioning.” says Liam Ryan, managing director of SAP Service and Support Centre, Ireland. “I don’t like the expense and people giving out about the cold, but it was more about its environmental impact. Merritt saw that as well, so as organisations, we gelled very well. He could see what we were about and we could see what he was about.”

Before they even began to consider how to achieve a comfortable, naturally ventilated space, the design team had to consider what it was they meant by ‘comfort’. “What we expected at the very beginning was that there would need to be a lot of flexibility within the different floor plates.” says Bucholz, “Because you had people in the building from Finland and people from Brazil and people from Brazil have a totally different idea of what comfort is to people from Finland. That’s something that the building has been very successful at – dealing with that idea that not everyone thinks 21 degrees is comfortable…What we’re trying to do in our building is make an organism that is much more human, much more flexible, much more adaptable, but at the same time, above all, one that uses less energy. All of these things are innovative in that they’re pushing society in a different direction, and it’s not a process that you finish when construction finishes. It goes on for a good time after that.”

The open plan offices have an integrated ventilation unit which provides fresh air & heating or natural cooling as required, with glazed areas shaded by external cedar brise soliel

The building consists of two 55m long, 3 storey blocks separated by a central atrium. The blocks are slightly offset from each other in order to eliminate the need for more than two internal fire escapes, thereby maximizing the efficiency of the floor plate. It is entirely naturally ventilated, relying on the central atrium to act as a ventilation ‘lung’. It’s this vital feature that provides the driving environmental force for the building and obviates the need for a mechanical ventilation system. David Walshe of IN2 Engineering Design Partnership explains that the system was developed in co-operation with German environmental engineers, Transsolar. “It relies on a combination of cross ventilation from the perimeter through into the atrium while the atrium itself is naturally ventilated at high and low level. In order that the natural ventilation be effective, it relies on two main features. The first element is extensive external solar shading to reduce heat gain, so there’s external, horizontal and vertical wooden shading brise soleil elements… Then the glazing is a high performance clear glazing. While it allows similar daylight contribution to standard double glazing, it has a clear film within its cavity that would be quite similar to low-e glazing, in the way that low-e glazing reduces heat loss. This high performance solar glazing reduces heat gain as well.” These elements mean you can capitalise on natural light while side-stepping the overheating risks inherent in an extensively glazed structure. “The film is on the outer pane of glass,” Walshe continues, “on its inner layer if you like, so it traps solar heat at that point and it’s reconducted to outside. Then, aside from the external façade, the building itself has exposed concrete soffits which are used as thermal mass within the building. In a conventional office you would have a plasterboard ceiling tile. When there are heat gains within the building, say if the sun is shining in and it’s hitting the floor and the walls and being radiated around the space, there’s very little mass within a plasterboard ceiling, so that that ceiling would heat up very very quickly. Concrete however is slow to heat up and slow to cool down, so basically the slab is slowly cooled down over the night time simply by allowing cool air in. It’s one benefit from Ireland’s climate that even on hot summer days, the temperature at night still drops, so you have temperatures around 14 degrees, and that’s very effective for cooling. If the daily temperature peaks at 25 degrees, the slab will probably peak around 21 degrees and will slowly cool down at night to 14 or 15 degrees. Likewise during the day, that concrete is heating up, and would hover at 18 or 19 degrees, which, with the internal air temperature around 23 or 24 degrees, is providing a cooling effect. It operates in the reverse of an underfloor heating system.”

What you have is a building which is engineered to understand prevailing conditions. All of these elements are entirely passive, yet taken together, they deliver an internal environment typically only achievable using mechanical ventilation. As David Walshe explains, there are automated units, but these are all small fans operating at the external envelope. There is no ducting; no air mass being pulled from one end of the structure to the other, and therefore no heavy power loads. “There are small fan units distributed around the perimeter. In a typical window mullion module that would be say, 1500mm wide, you have the fixed element of glazing, then in a 300mm wide section, there’s a manual opening mid-height, with a panel section with an external louver and a filter to allow draft-free ventilation during the daytime. Above that then, we installed a fan unit that has two purposes. During the summer time when you need night ventilation, the fans take air directly from outside and blow them into the building to cool down the mass and then in winter time, they were set up so the external air is mixed with the internal air…The problem with naturally ventilated buildings in winter time tends to be with people opening windows and getting drafts, but by mixing the outdoor and the indoor air, the fans provide a draft free environment.”

The thin plywood beam structure supports the glazed roof and provides solar shading to the internal atrium facades of the offices

Automation is only part of the story. A naturally ventilated building also relies heavily on human intervention. “The main natural ventilation strategy is manual opening of windows.” says Walshe. “The central sections of the windows are manually openable and that’s to enable user control within the space…There are motorised elements based on the internal condition of the atrium, but even with the BMS, we’re still leaving the localised control in everybody’s environment to themselves by having a manual opening window section beside them.” Allowing control of the environment to revert to from the BMS to the user isn’t just about expediting user comfort. Merritt Bucholz contends that it’s also about driving a change in attitude. “Effectively a lot of new buildings are about getting people to adopt practises that are more sustainable, so instead of relying on a building to deliver a particular environment, people actually have to engage with that environment. That’s exactly what you do at home. You open a window, you turn on the heating, you turn off the heating; you know your electricity and your gas bill every month and you act in a way which reduces them. I think it’s really about bringing the same level of consequentiality to the workplace and getting people to act in a way that creates a good environment.

Heat, when it is required, comes from two 275kW condensing gas boilers, says David Walshe. “The heating elements are simple convectors concealed behind panels below opening window sections, with a gap at the bottom and top of the panels which creates a high heating output performance. The heating system is operated using weather compensation – water supply temperature varies directly in accordance with external air temperature – to maximise the performance of boilers.”

The design incorporates three basic materials, all selected on environmental grounds. The concrete which takes a central role in the thermal mass strategy provides the basic structure of the building. Precast floor plates ensure that formwork wastage is minimal. The timber used in the atrium roof, the glazing system, brise soleil, cladding and doors all came from certified sustainable sources. “The windows are timber windows made in Longford.” says Bucholz. “What’s important about them is they’re made by a joinery company using FSC certified timber in Ireland. They weren’t imported from the UK or some more exotic place, they came from more or less down the road. I would also say that the construction ethos is one of simplification. While it’s certainly very highly engineered, it’s not a building that’s full of complicated details.”

The building is normally occupied over eighteen hours between 7 am to 1 am, with teams working 3 shifts. In addition to heavy reliance on natural light during the day, artificial light also plays a central role in the working environment. “The lighting installation within the office areas is managed and controlled via a lighting control system that applies a series of scenes throughout the day.” Ian Carroll of IN2 Engineering Design Partnership explains. “The scenes devised by the lighting consultant are intended to create differing effects at different stages of the day, raising and lowering the intensity and colour tone of the artificial lighting. The important factor as related to energy reduction is that the lighting control system allows the output of the luminaires to be reduced with a consequential reduction in input electrical usage.” The lighting within the building is time scheduled by zone, so the facilities manager can isolate and control different zones depending on occupancy. All luminaires within the office areas are fitted with Fluorescent T5 lamps, circulation areas, toilet areas and meeting rooms are fitted with CFL's, while occupancy sensors in the toilets keep energy usage here to a minimum.

The vent boxes to the atrium, housing a radiator panel, below a manual door to the louvred segment allowing for local user ventilation control, with a BMS operated panel which opens when the maximum temperature and CO2 control limits are reached

Lighting designed for the project by Bucholz McEvoy uses soffitts as a reflector to provide even illumination at desk level & make a bright comfortable space to work in

As far as energy consumption is concerned, the building is meeting its targets. Stephen Hall of SAP, who monitors this element of the building’s performance, says that consumption has dropped by 2% in the past year. With two years of energy use data now on file, he believes that there’s little further energy to be sweated from existing procedures. The kitchen and the EDP room are the big energy hogs, the latter because an overheating incident soon after commissioning lead to the installation of an air conditioning unit. “We lost two servers.” says Hall. “That can’t happen again.” He says that the bulk of that 2% reduction, along with all future energy savings, will come from behavioural change. “It’s come from informing people, from putting signage up…It’s about changing behaviour. People who are in meeting rooms leaving lights on, people leaving and forgetting to switch off monitors in the evening. We have our security guard on site 24 hours a day, so we have him going around checking that stuff is turned off when it should be turned off. We also have the lighting control system which is run through the BMS. We have different scenes that go out across the lights throughout the day, and that reduces energy consumption as well.”

So how do people like it? “It’s great.” says MD Liam Ryan. “If we were doing another building, I’d still go back to Merritt and ask him to do it again I think it’s a lovely building. If you look at first impressions of people who come for interviews, if you look at first impressions of people who spend time there, their first days and weeks, certainly the feedback is very positive.” Martin O’Kane, Deputy MD of contractor and developer Heron Brothers says that while this is the first time they’ve been involved in sustainable design, it will not be the last. “We recognised that it was going to be a new market and we wanted to get involved in it. We fully believe in the sustainable approach and we’ll be continuing to promote it now and innovate on all our developments as much as we can.”

The atrium, which is described as ‘a soothing internal landscape of birch trees, pebble beds and timber benches’ is the building’s key feature according to staff members Fergus Kelleher and Patricia O’Callaghan. “The building is very airy, very bright.” says Kelleher. “I like having a lot of windows; it’s great to have so much natural light coming into the building, and being able to walk through the atrium is extremely refreshing.”

“It’s very nice out there.” says O’Callaghan. “People would go out there for tea or coffee if they’re having a break, it’s very relaxing, it helps with the airflow through the office area and it’s really nice to walk through.” Getting the comfort level right has been tricky. “There were a few teething problems,” she goes on, “but that’s always going to happen no matter what kind of building you’re moving into. I think people are used to it now. It’s difficult to keep everybody happy because there are so many different people from different countries and different climates; too hot for some, too cold for others.” Particular difficulties have arisen on the hottest summer days. “It’s difficult to regulate the temperature throughout the building.” says Fergus Kelleher. “On the top floor, a lot of people will say that it gets too warm in the summer. On the ground floor, it might be just right. It is a difficult building to regulate all rooms to the temperature that people would like.”

The unheated atrium contains bridges with adjustable screens covered in aluminium backed fabric which locally modifies the environment, allowing breakout spaces to be comfortably used in winter time by reflecting heat inwards and by shading in summer

The thin plywood beam structure supports the glazed roof and provides solar shading to the internal atrium facades of the offices

“We have had [initial] teething difficulties.” says facilities manager Jarlath McGagh. Again, he points to temperature rises on the hottest summer days. Together with the environmental engineering team, he has been working on the ventilation system to try and deal with the issue. “The temperature can rise very quickly [without manual intervention]. We do have to interfere, for want of a better word, to open up as many vents as possible, to get as much air as possible into the building, to try and force a stack effect. We’ve also put blinds on all the windows and that has helped a lot…We’ve found it useful too to group nationalities in one area, so one area can have it one way and another area a bit cooler. That seems to have worked quite well.”

David Myers, of construction and property consultancy Gardiner & Theobald, provided quantity surveying services on the project. He acknowledges that there have been problems. “I think it’s down to a variety of factors. One, there isn’t a sufficient induction period within the space, also there are expectations that are incorrect. The reality is that until you’ve been in a building for the four seasons, it’s only then you truly know how the building works. The expectation seems to be you walk into the building and it’s all working perfectly on day one. Certainly on the SAP building, there would be a dichotomy of views. The facilities management side would be saying that things didn’t work, the building side would have said that the carefully instigated controls and balances on things like valves and ducts were all unilaterally changed and then the whole thing blew out of sequence.”

Architect Merritt Bucholz believes that the issues that have arisen since commissioning do not stem from either a failure of design or a failure to engage with the design. “To look at it in the first instance as a failure is the wrong attitude…Design is not a panacea for the world’s problems, it’s a way of reducing our dependence on natural resources and that’s not territory that people are very familiar with. People don’t expect to have to change the way that they are, but they do and that’s the reality of it. One of the big areas that needs to be developed in a more sophisticated way is facilities management. I think typically facilities managers take the attitude when they go into a project that everything’s automatic, that there are computers that control things, but the reality is that all of these things are human things. The world is a human place. Spaceships don’t get to the moon because we hope for the best, they get there because humans make decisions to get them there.” Any building is an instrument, he maintains, and must be played like one. “There’s a lack of joined up communication between various control systems, that control lighting, CO2 and ventilation, so there’s a kind of requirement that the human be the glue between things that don’t necessarily talk to each other.”

He points out that the building was actually designed to be uncomfortable for a small proportion of the year. CIBSE, the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers publishes a set of standards for naturally ventilated buildings, and it is according to these standards that the building and its systems were calibrated. “The temperature cannot exceed 25 degrees for more than 5% percent of the occupied year. Now the working hours in SAP are very long; they’re in at seven in the morning and finish at one in the morning, so that’s one of the most onerous criteria to meet. That’s why we went through this simulation process which included CFD analysis, building fabric analysis, temperature analysis, shading analysis… These criteria mean that the building will reach 25 degrees for 5% of the year. It will. It’s not that it won’t, it will and the clients are aware of that.”

Once again, Bucholz returns to the idea that people can no longer see themselves as passive agents in an environment that lies beyond their control. “Environments are something people create, not something they’re given. We cannot take this thing for granted; environment, temperature, climate. We cannot say, ok, I expect this to happen with no action from me, we cannot this is the way I’d like the building to function. People have to engage with the environment.”

Selected project team members:

Client: SAP

Developer: Heron Property ltd

Contractor: Heron Brothers ltd.

Architects: Bucholz McEvoy Architects

M & E engineers:

In2 Engineering Design Partnership

Quantity surveyors: Gardiner & Theobald

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Ventilation

- air conditioning

- Bucholz McEvoy

- passive

- Transsolar

- FSC certified timbe

Related items

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

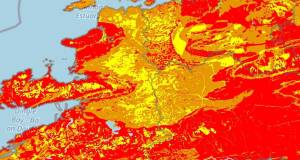

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation -

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds -

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel -

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches -

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds -

Study confirms “systematic inequalities” in indoor air pollution

Study confirms “systematic inequalities” in indoor air pollution -

New app for remote control of Nilan Compact P

New app for remote control of Nilan Compact P