- Eco Housing

- Posted

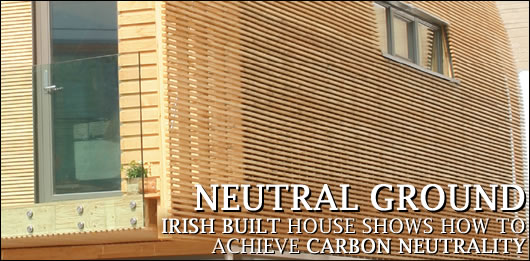

Neutral Ground

Watford, just over 30 kilometres north of London, is now home to an aspirational new house, developed by an Irish company, designed to completely remove carbon emissions from the home. Jason Walsh visited the site to learn moreThe house lies in the grounds of the Building Research Establishment's testing centre, a former government site, and is named the Lighthouse. The Lighthouse is Kingspan Century's mould-breaking new model for zero carbon housing.

Developed as a response to the British government's 'Building a Greener Future: Towards Zero Carbon Development' strategy, the zero carbon, 93.3m2 two-and-a-half storey two bed Lighthouse, developed by Kingspan Offsite, meets the plan's requirements for 'level six', the top tier of the plan to eliminate carbon emissions from the home.

This is quite a few years ahead of the legislation: level three calls for a 25 per cent improvement on 2006 regulations by 2010 while level four demands a 44 per cent improvement on 2006 regulations to be in place by 2013. Level six, zero carbon, is due in 2016 for private house and 2013 for social housing. Here and now in 2007 Kingspan has met level six with the Lighthouse.

But what, exactly, is a carbon neutral house? And how does the Lighthouse achieve this status?

According to the British government at least, a carbon neutral house will need to deliver zero carbon (net over the year) for all energy use in the home – cooking, washing and electronic entertainment appliances as well as space heating, cooling, ventilation, lighting and hot water.1

The Lighthouse achieves its carbon neutral status through a range of measures including higher build standards and offsetting via the use of renewable energy.

The fabric of the building is highly insulated and airtight. The high level of insulation means that the Lighthouse requires 60 per cent less heat than a traditional building of a similar size. The building is constructed using Kingspan's TEK building system based on structural insulated panels to deliver the required high levels of thermal insulation and airtightness.

A mechanical ventilation system with heat recovery keeps the house fresh and warm and photo-voltaic solar panels contribute to meeting the occupant's electricity needs.

Reliance on artificial light is reduced by designing for the provision of large amounts of daylight.

Solar thermal panels heat water for the home's owners, while water efficiency devices such as rain-water harvesting for WC use reduce waste and a wood pellet boiler provides additional space heating to the house.

PV solar panels for generating electricity are a key part of the Lighthouse's claim to carbon neutrality

The sloped roof allows for maximum exposure to sunlight for the Kingspan estimate that this will be greatly reduced in future as the technology develops

Timber used in the house is sourced from managed forests and other materials used in construction include recycled components. Additionally, the house's landscape design specifies permeable paving and sustainable drainage.

Kingspan claims that overall the building exceeds current Irish energy standards by almost 100 per cent.

Unveiled by British housing minister, Yvette Cooper, the Lighthouse has been awarded a stamp duty exemption certificate as a prototype carbon neutral property, creating a financial incentive for buyers and developers. As it stands today, the Lighthouse is the first dwelling to meet the highest standards laid out in the government's code for sustainable homes.

Architecturally, the building is striking. A timber exterior, the main elevation is barn-like with a deeply pitched roof set at a 40 degree angle. The eye-catching design attempts to marry modernity with the use of traditional materials. The sweeping roof which does so much to define the building, providing its signature, allows for spacious, open-plan, top-lit, double-height living.

Designed by Alan Shingler of architectural practice Sheppard Robson in London, the building situates the main living areas on the first floor in order to make use of natural light to provide an attractive space. This topsy-turvy design sees the sleeping areas – two bedrooms – located on the ground floor, but it certainly does result in a well-lit living area and kitchen. The top-floor atrium is a small but flexible space suitable for uses including a home office.

Carbon challenge

By building this house, Kingspan Century hopes to draw a line in the sand and challenge developers to cross it: "The first objective is one of proving the point that it can be done," says Gerry McCaughey, Kingspan Century's chief executive. "The British government took a stance that was very forward-looking and we've proven that it's technically achievable in 2007."

Despite Ireland's relatively late awakening to sustainable building, McCaughey is confident that the results of the 2007 general election will have a positive impact on the country.

"It's very important to us that regulations are improved as time goes on," he says. "The regime change that has taken place has been black and white," says McCaughey, noting a renewed commit-ment to reducing the heating demand of new homes. "The semantics before were 'up to 40 per cent', now it's 40 per cent. The minister has said that it's 40 per cent minimum and 60 per cent by 2010.

"I would be hopeful that we'll be close to the UK regulations by the time that the government has served its time," he says.

McCaughey who represents one of the Irish building industry's largest firms is clearly enthused by the entry of the Green Party into the cabinet: "If you look at the record of the Greens in Fingal it hasn't been one of blocking housing being built, their view has been 'let's build sustainable communities.'"

Of course, McCaughey has a clear commercial interest in tougher energy requirements – at the very least Kingspan would doubtlessly be happy to get a major order for its houses and a plan in line with Britain's level six would arguably give Kingspan, and other non-block-work = builders, a competitive advantage.

McCaughey dismisses this, pointing out that standards are the issue, not materials: "In Germany fifty per cent of passive houses are blockwork.

"Hollow block is dead in the water. Mainstream masonry techniques will have to evolve and develop. The timber frame industry has shown its willingness to move forward," he says, arguing that one of the problems with construction is inertia and an inability to evolve. "Building is probably the most conservative industry on the planet. It very rarely leads, it usually has to be dragged. The hollow block was brought up in the Oireachtas when I was a schoolkid and here we are in 2007.

McCaughey is critical of the legislative framework in which development has occurred up until now in Ireland: "The urban sprawl like a fungus growing out from Dublin was a missed opportunity. Ire-land will never go through the spate of construction that took place in the last ten years," he says.

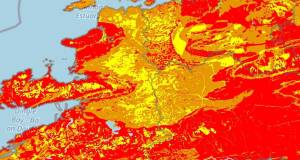

This is a popular opinion and one that is seemingly reinforced by many people's daily experience of commuting and city life, but it is also not the whole story. During the period 1990 to 2000, a period much of which is synonymous with construction, notable increases in land cover area include arable land, urban development and artificial surfaces and forested land. Urbanisation and development have occurred, to be sure, but they are not the only increased component of land cover, they are not even the main one. As the Environmental Protection Agency states: "There was also an increase of 23 per cent in the area of forested land. These increases were mainly at the expense of pasture, mixed farmland and wetlands." 2

Gerry McCaughey on the BRE site with the Lighthouse in the background

Moreover, arable land permanent crops accounted for 66.8 per cent. Artificial surfaces accounted for a mere 1.9 per cent of land cover in Ireland in 2000, according to an official European Union study. This is up on 1.5 per cent in 1990 but the high growth in development during the period had a negligible impact on overall land cover.3 When considering these numbers it is important to understand that, despite lasting construction after 2000, including year-on-year increases in house completions, the economic boom is generally associated with the period beginning 1994. Indeed, from 1994 to 2000 Ireland's gross national product (GNP) rate growth ranged between six and eleven per cent, be-fore falling in 2001 and early 2002 to two per cent, the level at which the economy had been growing in the pre-boom early 1990s, and then returning to an average of around five per cent. Accepting that building continued at a high rate post-2000, it is far from certain that Ireland can be described as a highly urbanised country. Moreover, it is vital to note that many inner city areas that are now lauded for their high density living were once outlying suburban areas themselves and others were overcrowded slums. Sprawl, as a term, is arguably too emotive to make much of a positive contribution to any planning debate in Ireland.

A 2006 report indicates that urban land cover is at four per cent,4 though it is unclear if the method-ology is comparable. However, even this increased figure makes Ireland one of the least urbanised countries in Europe. The same report notes urban land cover at 12 per cent in France, 20 per cent in Italy and 28 per cent in Germany and the Netherlands.

Data for the period 2000–2006 is due early next year. It will be interesting to see if development post-2000 has followed a model of low-density, often one-off houses, which are often blamed for contributing disproportionately to traffic congestion, energy use and other negative factors associated with sprawl.

Nevertheless, Kingspan is clearly geared-up for a change in Irish building: "We have missed an incredible opportunity – an urban blight on the landscape [and] from a CO2 perspective, we have created incredibly low standard buildings."

McCaughey does admit that the Lighthouse, with its prominent curved roof, does not look like a typical Irish house and that the striking design is not simply art for art's sake: "Everybody involved in the project will tell you the technical difficulties in achieving a zero carbon house do impact on the design of the house," he says.

For example, the curve of the house resulted from the requirement of current technology to have the PVs at a 40 degree angle.

"It will take time for the technologies to develop and become mainstream," says McCaughey. "That will probably be down to twenty square metres in the next two years [and] the technology of using transparent PVs is moving forward."

Despite the high-design and relatively high-tech nature of the Lighthouse, the building has piqued the interest of developers: "We're already in advanced discussions for sixteen of these houses, using this design, in Ireland. I'm 90 per cent sure it will go ahead.

"They'll be in the south Midlands. The developer has said 'I want to put down the marker that I was here first'. He believes that, in the future, there will be more social and affordable housing being organised by the local authorities themselves."

Rainwater harvesting is used to contribute to the house's water needs

McCaughey puts this down to the presence of a Green Party minister holding the environment portfolio: "I think that since John Gormley was appointed the penny has dropped with a lot of developers. By the end of this particular five years you will see a different approach to house-building in Ireland. The tent at the Galway Races won't be as important as it was."

The approach that the Lighthouse points to is one that could make a contribution to stabilising the country's finances: "When the government is buying carbon credits with taxpayers money it is in-cumbent upon them to look at ways of avoiding that," he says, arguing that one of the most effective way to reduce this is by creating more energy efficient homes.

"I would ask that the incoming administration look at what has been achieved by an Irish company and see what levers the British government has used, instead of re-inventing the wheel. There's a lot there we can learn from."

Biofuels in the form of wood pellets are used for space heating

Future gazing

So just what are the chances of the Lighthouse leading a renaissance in construction either in Ireland or Britain?

McCaughey makes a convincing argument that the British government has been more forward-looking in its housing policy.

In this regard at least, he's probably right. Unfortunately Tony Blair has presided over an administration that has seen house-building decline so badly that the UK is now facing a very severe housing shortage – and there are few signs that this policy will change under Gordon Brown.

Whatever the failures of Irish housing policy and planning regulations – and there are plenty – at least houses are actually being built. The same can scarcely be said about Britain.

Between 2004 and 2030 Britain's population is estimated to grow by 6.5 million.5 When combined with lower household sizes, an estimated five million new dwellings will be required in the next twenty-five years.6 And yet with a mere 161,800 new dwellings, 2001, the year of Mr. Blair's re-election to a serve a second term as prime minister, saw the lowest number of house completions since 1924 (excluding the period of the second world war). According to one commentator, 200,000 new homes are needed each year for the next 25 years in the Greater London area alone.7

Windhager wood pellet boiler

Once can't help wonder if the British government plans to achieve its stated goal of carbon neutral status for housing by not building any houses in the first place.

More recently, Ireland (excluding the six counties) with its 4.2 million people, an underpopulated country by any measure, saw 90,000 house completions in 2006.8 The UK, with a population of 60.2 million, saw 223,000, leading one report = to note that "the overall under-supply of housing will remain a feature of the market."9 The report continues: "[...] the number of completion levels grew by around 2 per cent in 2006, a disappointing figure given the government’s aims to address the current housing shortage. Changes in demand structure, driven by demographic and social factors such as increasing migration levels, an ageing population and a growing number of single person households, have led to a mis-match between supply and demand of housing."

The reasons for this disparity are manifold. On the Irish side of the equation, population growth and immigration and an economy fixated on building have driven demand. In Britain NIMBYism and snobbery run rampant with the full support of local and central government, ensuring that too few houses are built where they are needed, that is in the south east of England. Despite the British government's oft-stated desire to build more homes for its people, little seems to actually be being built. Preservation of England's 'green and pleasant land' is the usual reason given for this with conservative pressure groups such as the tweedy, aristocrat-stuffed, Campaign to Protect Rural England – the para-agrarian wing of the Conservative party – demanding a continued moratorium on house-building in the so-called 'green belt'. This despite the fact that, for example, in the south east of Eng-land 9.7 per cent of all land is woodland, 41.8 per cent is arable and horticultural and 27.5 per cent is grassland – this in the most densely developed part of the UK. So much for 'urban sprawl'.10 In fact, taken as a whole, less than ten per cent of land in Britain is developed. This, in conjunction with other disincentives to industry, such as cash-grabbing by local authorities in return for planning ap-proval under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act (1990) and the rampant short-termism manifest in contemporary capitalism, fixated as it is on delivering quick returns to increasingly boisterous and belligerent shareholders.

The main living area on the first floor of the Lighthouse

Stairs from the main first floor area to the mezzanine level on the second floor which provides additional flexibility useful, for example, for home working

Put simply, in the current climate, the British construction industry can make plenty of money selling fewer houses. This in turn causes a shortage which drives up prices of both second-hand houses and the relatively few new developments and increases speculation. When combined with the stigma associated with social housing and even private renting, it is clear that what Britain is facing is an over-valued market for second-hand homes based on unnecessary scarcity.

Today in Ireland the situation is different, but not as a result of 'overdevelopment' – the disparity be-tween perception and reality in the British statistics should give some indication that while 'sprawl' and distaste for concrete is a popular concern for the sybaritic classes, its significance lies in realm of perception, not any concrete reality.

Instead, the difference in Ireland is a political climate that is not hostile to house-building – at least not yet. The 2007 general election saw the appointment of two Green Party ministers and one minister of state. Among the appointments was John Gormley as Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. In this role, Gormley will be directly responsible for the future of house-building in Ireland. At this point, the Green Party has not shown any inclination to play the NIMBY card and, in the case of recent developments in Fingal, Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown and Wicklow, has been supportive of large-scale development so long as energy and CO2 issues are taken into account.

In fact, the Green Party's 2007 election manifesto promised the building of 10,000 social and afford-able housing units a year.

Nevertheless, anyone desirous of zero carbon houses in Ireland will need to prove their viability, both in practical terms and in terms of market demand, to developers. Some moves in this direction are being made: a change to Part L of the building regulations demands a 40 per cent reduction in energy used for space heating and hot water in the home while the Green Party is also committed to reduce energy use by 60 per cent by 2010.11

Whether these developments, along with changing market conditions and increased construction of social and affordable housing under the aegis of the Green Party, are enough to stimulate demand for zero carbon housing in Ireland remains to be seen.

There's no doubt that the Lighthouse is something of a PR coup for Kingspan Century – the company has delivered what they would doubtlessly describe as tomorrow's house using today's technology and it's certainly a noteworthy achievement in its own right. It will, no doubt, be a positive development if the proposed sixteen Lighthouses are built in the Midlands, as the developer says 'putting down a marker', but moving forward to a situation where the vision underpinning the Lighthouse becomes the norm, however, is likely to prove a more difficult hurdle.

1 Department for Communities and Local Government, 'Building A Greener Future: Towards Zero Carbon Development', December 2006

2 Environmental Protection Agency, 'Biodiversity and land cover', see: http://www.epa.ie/environment/biodiversity/landcover/

3 See the following map for more details:

http://terrestrial.eionet.europa.eu/CLC2000/countries/ie/full

4 See: Hennigan, Michael, 'State of Chassis: Artificial restriction on land supply puts Ireland and UK at bottom of property league in Developed World; Irish urbanisation at 4% is among Europe's lowest', Finfacts: http://www.finfacts.com/irelandbusinessnews/publish/article_10005314.shtml

5 Office of National Statistics, 'United Kingdom population set to pass 60 million next year', 30 September 2004

6 Abley, Ian, 'If London is so great, why not build more of it?', Rising East, December 2005, University of East London

7 Ibid.

8 Davy Stockbrokers, 'The Irish economy - An Assessment of Risks and Forecasts 2008–2010'

9 AMA Research, Housebuilders Market Report – UK 2007

10 Office of National Statistics, 'Land cover by Broad Habitat and Standard Statistical Regions, 1998'

11 Green Party, Draft Programme for Government: http://www.greenparty.ie/en/library/draft_programme_for_government

- Articles

- Eco Housing

- Neutral Ground

- Rainwater Harvesting

- Carbon Neutral

- wood pellet boiler

- heat recovery

- Ventilation

- McCaughey

- emissions

Related items

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

Much ado about nothing

Much ado about nothing -

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030 -

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation -

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds -

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel -

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches