Venting opinions

Whilst great strides are being made in upgrading energy performance requirements under Part L of the Building Regulations, the issue of ventilation has remained largely ignored by legislators for years, leaving designers with antiquated standards to work to. At its worst, efforts to air-tighten and increase the insulation of homes is being undermined by the absurd practice of knocking holes in walls. John Hearne looks into what changes need to be made to modernise Part F.

Ventilation is about health. When the changes to Part L of the Building Regulations come into effect on July 1st, and Part F has not caught up, we are in a potentially grave situation. “The current Part F allows for holes in the wall as supposedly adequate ventilation for dwellings.” says architect Jay Stuart. “The modern version of that is trickle vents in window frames, both of which allow the wind to blow cold air straight in during the winter, causing drafts and discomfort, and also heat loss, which means that people tend to block them up. Then you’ve got no ventilation, then you get high humidity, and with cold surfaces you get condensation, and then you get mould starting to grow, from that you get potentially very dangerous spores like asperilligus, which can cause allergic reactions in people, and death. We are talking death here.” It’s a stark warning, but one which places the critical issue front and centre. Even assuming a minimum level of compliance with the regulations due to take effect from July, new buildings in Ireland will in most cases likely see a very substantial increase in their degree of air-tightness. Knocking a hole in the wall as current regs stipulate will make a nonsense of the advances already made. Sealing up the building isn’t going to work either.

None of which is to suggest that the current code is only a failure in the light of changes to come. Part F has already failed on a variety of fronts. As it stands, Part F reference documents SI 581 (2002) & TGDF (2002) state: ‘Adequate means of ventilation shall be provided for people in buildings, including adequate provision for the removal of water vapour from kitchens, bathrooms and other areas where water vapour is generated.’ The TGDF goes on to acknowledges in paragraph 1.3 that ‘Ventilation to achieve the objectives set out in Paragraph 1.1 may be achieved by natural ventilation, or through the supply or extraction of air by mechanical means, or by a combination of these methods. The guidance in this document relates only to non-complex buildings of normal design and construction where natural ventilation constitutes the primary means of ventilation.’ Shane Miller, managing director of Quality HRV says that these protocols have led to a situation where the vast majority of new builds in the country have been designed and built with holes in the walls to provide incoming fresh air and mechanical extract in bathrooms. “This strategy is costing Ireland as an economy an unquantifiable amount of money every day. Bring in cold air randomly, heat it up and throw it outside. All of the guidance given in the document relates to how big the openings for fresh air should be and the capacity of the mechanical extract fans.”

Seamus Hoyne of Tipperary Energy Agency sees the fallout from these technical guidance documents every day. “You might have projects where they have gone and increased insulation levels above the norm and then they are going in and putting in the hole in the wall. They don’t realise that the heat loss through the ventilation is as much as through the fabric insulation levels.” Jay Stuart maintains that the traditional ventilation solutions as specified in the technical guidance documents will not work at all in particular circumstances. “I don’t think that holes in walls should be allowed. They don’t work, and if you look at the physics of it, you’ll see why they can’t work in a single sided apartment. It’s only going to get either positive or negative pressure, so it’s only going to be pushing air either in or out of one hole. That doesn’t work. You need an in and an out.”

Approved Proair installer Jana Hutirova puts the finishing touches on a heat recovery ventilation installation in a house in Galway

The consensus in the industry is that radical change is vital, both in the overall approach to ventilation, and in the minutiae of the specifications themselves.

It’s about air quality

While Irish regs focus on fresh air and water vapour, many European jurisdictions focus instead on that central issue; health. “In any of the Scandinavian countries,” says Shane Miller, “the first line would be, the first and foremost objective of the regulations is to provide a comfortable and healthy indoor climate for the occupants of the building.” Ciaran King of MTD Solutions also believes that this approach is the way forward. “We believe it should deal with the indoor air quality, not just the ventilation. That’s how it should be specified.” So is that the direction we should take? Define a minimum air quality – say parts per million of pollutants – and leave it at that? It’s not that easy, says King. Outdoor air quality varies so widely that we can’t legislate with so blunt an instrument. We have to get down to the detail.

The mindset has to change first

Ventilation doesn’t save you money. “We’ve noticed a change in the last six months,” says King, “where people have heard about heat recovery and want to know what it is. The irony is, the one question everyone is focused on is how much will this save me? We tell everyone, absolutely nothing. Your insulation gives you your energy saving; ventilation is necessary. The more insulation you have and the stronger the air-tightness is, the more you require ventilation.” If you insulate, you must ventilate. The difficulty for the industry is that mechanical heat recovery ventilation is not cheap. “You’ll spend more on MVHR than you will on insulation to achieve Part L.” says Jay Stuart. “On that basis alone, resistance is going to come back very strongly from elements of the industry.” The good news however is = that passive ventilation systems are available, they are cheaper and offer a viable alternative to MVHR.

Innovation

As it stands, the current Part F discourages the construction of high quality buildings. “There was a time,” says Shane Miller, “when the discussion about mechanical ventilation with heat recovery centred on whether or not it actually complied with building regulations. All it says in the guidelines is to put holes in the walls, so when you suggested taking the holes out of the walls, people were saying, no, they’ll never sign that off.” One of the key characteristics of the current technical guidelines is that there aren’t that many. The equivalent UK document runs to 54 pages. Ours run out of steam after twelve. While it’s easy to find critics of the UK technical specifications, most will acknowledge that it at least recognises the existence of mechanical heat recovery ventilation, and gives specific guidance on how to make it work to satisfy engineers. “We have a situation here,” says Miller, “where ventilation strategies have been tried based on the bravery/intelligence of individual designers with the best advice possible from the industry. Without specific guidelines it is difficult for the industry as a whole to adopt the newer technologies with confidence. We have also created a situation where snagging a building is difficult as the independent engineer representing his or her client has no reference material to go on, only their professional indemnity, gut instinct and professional experience.

Designed passive ventilation with heat recovery, such as the Dwell-Vent system, seen here in Jay Stuart’s Easton Mews housing project, has great potential. The system combines (bottom of page) supply air windows and (above) a passive stack effect using wind-cowls

Specifically, he identifies four forms of ventilation that must be specified in detail in any new regulations.

• Natural ventilation with mechanical extract

• Passive stack ventilation

• Hybrid natural ventilation

• Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery

Essentially, we need technical guidelines which stipulate designed ventilation systems to the exclusion of all else. “We must have designed systems,” says Jay Stuart, “and in order to make sure that they’re energy efficient, they should have heat recovery. That doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be a fan with a heat recovery unit. There are passive options and there are different ways of doing heat recovery. The government in revising Part F must keep the door open for innovation and alternative methods of providing adequate ventilation.” Again he stresses the importance of detail and takes as an example, how a guideline might emerge around supplying air to a bedroom. “A developer could reduce his costs by only having the ductwork distribute in the hallway and have the grille that dumps the air directly above the entrance door to the bedroom. With the extract in the bathroom, you could get short-circuiting. The air wouldn’t actually ventilate the room…so you need to have requirements for actual air movement and there needs to be some way of testing that or ensuring that designs achieve minimum standards. That might mean being prescriptive about inlets and outlets being at extreme ends of rooms, away from the extract point.” He advises adopting a cynical meticulousness in drafting the regulations. “What’s the builder/developer going to do to undercut his costs? What is somebody going to do who doesn’t understand what we’re trying to achieve? We have to prevent that from happening by saying you can’t do that.”

One point made repeatedly by nearly every contributor is the disconnect in maintaining separate sets of guidelines for energy, ventilation and heating appliances, respectively Parts L, F and J. “F states that we should have adequate ventilation,” says David McHugh of Proair, “mainly provided by holes in our walls or windows and J states that fuel burning appliances should have permanent wall openings to provide for combustion air. This is all very laudable but they both conflict with Part L which says we should construct our buildings as airtight as possible as airtightness is key to conserving energy. It makes no sense to compromise it by punching holes in external walls. It is time we took a more innovative look at both combustion air and ventilation problems.”

Without adequate ventilation in wet rooms in particular, mould growth will occur

Ciaran King’s experience of the illogical separation of these three interdependent elements of the regulations is telling. “We’ve had BER testers ring us up saying we were talking to one of your agents, we were going to use one of your units but to be honest we’re not going to do it because we’d lose the rating on the house. Ok, I tell them, so bang your four holes in the house, increase your heating system by 40% to cope with it and see if you get the same rating. They haven’t realised that when they designed the software for calculating the energy requirement on the house, it’s assuming the house is airtight, then they put in the unit, and if the house, depending on its size is on the border line, any small amount of energy produced a year can push it into the next rating…What’s happened with Part L is they’ve forgotten about this hole in the wall calculation, so everyone is designing their heating system assuming the house is air tight, then when they add this extra continuous electrical component, it can put them into a lower energy rating, but if they take it out and put in the holes in the wall, they have to increase the heating load to heat a house that isn’t airtight, and they might as well throw out most of the insulation because there’s no point in having it. That’s where there’s an overlap between Parts L and F, and it only happens in Ireland and the UK.” Many in the industry are also unhappy with the decision in revising part L to set the minimum air permeability at 10m3/(h.m2) Many MVHR companies specify a minimum figure of 4m3/(h.m2), while at least one will refuse to install a system in a dwelling which fails to meet this minimum standard. Whatever the figure is, it is vital that it be known and fed into the calculations which will ultimately determine whatever ventilation strategy employed.

“We would see the sense,” says King, “in combining Part F and L, even if it was phrased as simply as, you’ve insulated to a certain level and it’s air tight construction, you must have either a mechanical ventilation system or a passive system with heat recovery, to a minimum of 80%.” The disconnect between the two sets of regulations once again muddies the water and makes it difficult to achieve a balance between the energy consumption of a MVHR system and its capacity to recover heat that would otherwise be lost. King is critical too of the way in which Appendix Q of SAP – which will obtain until Appendix Q of DEAP is developed – deals with the central issue of evaluating the energy performance of new technologies for inclusion in DEAP assessments. “It gives you watts per Litre per second usage for the fan. Basically that is useless, it’s the equivalent of saying a car drives at 40 miles to the gallon. Is that driving in the city? Is it towing a truck? Every house is different. But it’s a start and it’s a guide… They should be stating that the HRV system or the passive ventilation system is given between 0.3 and 0.5 changes of air per hour in the dwelling. Those are the design parameters that have been used in the rest of the world on sizing a system.”

Condensation in roofs

The current regulations devote an entire section to preventing excessive condensation in roofs. “This section could be eliminated in any revision if we carry out part L to its limits.” says David McHugh. “With ready availability of breathable felt nowadays, any water vapour existing in cold roofs can escape on sunny days. If an attic has the required amount of insulation then the air in the attic will be as cold as outside and not reach dew point. If the building underneath is airtight then no moisture generated by occupants will be able to migrate to the attic. Currently we have a great problem of over-ventilation of roofs and in windy weather there is excessive air in movement in many roof spaces. We tend to ventilate soffits at about 1 meter centres. The result is that on windy winter nights, movement of cold air causes drafts in less than fully air-tight rooms.” This, he points out, introduces cold air into rooms, usually through light fittings (notoriously downlighters). In addition, insulation typically relies on its ability to hold air or an insulating gas in order to give a positive effect. Air movement above the insulation has a negative impact on insulation performance.

A Quality HRV ventilation system with two of its polyethelene ducts in place during installation at a house in Blackrock, County Dublin

Open fires

Once again, we’re crossing into Part J, but given the current regulations in relation to open fires, not to mention their popularity, their existence cannot be ignored by a functional ventilation strategy. “It is time we took a more innovative look at both combustion air and ventilation problems.” says David McHugh. “It is now possible to buy wood stoves and gas fires with independent air connections and or balanced flues. Even flame effect gas fires are now available with balanced flues. This leaves solid fuel burning open fires. Perhaps it is time to bite the bullet and ban them altogether. After all what can be burned in them? Not rubbish, not coal and not turf as all have obvious disadvantages.”

“I think basically no. We can’t have them anymore.” says Seamus Hoyne in Tipperary Energy Agency. “You’re getting 80% heat loss through your open fire as well as the additional ventilation losses. We haven’t looked at it in the context of the new building regulations yet but it’s going to be very difficult to have an open fire and be compliant. If we tighten up the ventilation heat loss, then it will be impossible.” This is the issue most likely = to attract adverse public reaction. While it may be possible to specify an open fire that will not run counter to the core ambitions of Parts L and F, one of the difficulties here relates once again to the unhelpful division of the regulations.

“The principle is dead.” says Shane Miller. “It has to be, for several reasons. If you take any of my customers, they’re building airtight houses, we’re sticking in a ventilation system, and in order to have sign-off by an engineer, to say it’s compliant with the regs, they need to have a big hole in the wall in the room where the fireplace is…The problem with an open flue fireplace is the day it’s lit, it’s 15% efficient and the day it’s not lit it’s minus 100% because of the hole.” He believes that we have to bring all fires to the internal combustion stage, using – for example – a balanced flue. There are open fire solutions involving a more sophisticated ventilation system, together with a high degree of sealabilty when not in use. But whether or not these can be specified in compliance with the current Part J remains to be seen.

No building control

It’s a fact that may fall outside the remit of the regulations themselves, but the absence of any meaningful building control in Ireland inhibits the effectiveness of the most far-reaching technical guidelines. “I’ve been into many recently constructed dwellings where the ductwork is many metres away from the external walls on single aspect apartments.” says Jay Stuart. “The fan is bottom of the range cheap and can’t possibly push the air that far. The ductwork goes up and down and all over the place, and probably leaks, it isn’t tested and I don’t think you’re getting any actual ventilation at all. I’ve been in two major sites by major developers and well known contractors where they’ve got such incredibly bad condensation problems, and they’re not sure what to do...I have been present when those extract fans have been tested and they’re actually generating 15% of the airflow of what the manufacturer’s data sheet says it is.”

Not only are open fires one of the least efficient means of heating a building – they also contribute to the problem that they fail to solve by requiring a hole in the building envelope to function

What they do elsewhere - UK

In the UK, the basic requirement is even more antiquated than in Ireland. UK ADF 2006 states: “There shall be adequate means of ventilation provided for people in buildings”. It is however a significantly more comprehensive document for a number of reasons. Section 0:07 states that “Ventilation also provides a means to control thermal comfort and this, along with others, is considered in Part L”. Sections 0:10, 11 and 12 make distinctions between the infiltration and purpose provided ventilation, indicating that the former should be minimised where possible and the latter be properly designed. Infiltration levels of 3-4 m3/h per m2 at 50Pa are acknowledged as achievable targets and that the ventilation guidelines given in the ADF2006 are appropriate down to these levels of airtightness. The technical guidance covers basic principles of ventilation. It is interesting to note that three of the accepted methods work on the same principle highlighted in the Irish TGDF though good guidance is given on calculating ventilation rates for each of the technologies based on ventilation effectiveness.

What they do elsewhere - Finland

Due to the harsher climate, it became apparent to the Finns at an early stage that ventilation was more than just air in and air out. D2 NBCF states: “As a whole, buildings shall be designed and constructed in such a way that a healthy, safe and comfortable indoor climate can be achieved in the occupied zone under all normal weather conditions and operational situations.” This is a significantly different approach to ventilation as it determines a lot more than just the ventilation conditions of the indoor climate. It brings in thermal conditions, indoor air quality, acoustic conditions, lighting conditions & ventilation requirements. Again because of the climate there is a focus on airtight construction though reference to airtightness is made exclusively in another document called Thermal Insulation of Buildings (2003). “The air-tightness of the building envelope should be good enough that the ventilation system in the building is able to function as designed. If necessary, the structures must have a separate air barrier. Particular attention should be paid to the design of junctions and leads-in in structures and to the thorough construction work.” It goes on to clarify this statement by saying “In respect of functioning of the ventilation system, air-tightness of a building should be preferably close to the value of n50= 1 1/h” (one volume of air in the building is flowing through the building envelope in an hour when the pressure difference between the inside and outside air is 50 Pa).

So what next

The new Part F has been drafted and will go to the Building Regulation Advisory Body – a statutory body set up as designated – ahead of a meeting with the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government set to take place on March 10th. The public consultation process should kick off immediately after this meeting. Some forty-seven submissions were received during the public consultation period that preceded the adoption of the new Part L. According to EU competition law, the regulations cannot be signed into law until a period of three months has passed. “Our hope,” says a spokesman, “would be that literally after the three month period expires, the minister would be ready to sign. Our deliberations on the submissions to come should have borne fruit...When we put our proposals we always bring to his attention what issues were raised during the public consultation process, we tick off what we believe should be taken on board, what we believe shouldn’t and if we don’t think so, why we don’t think so, and the minister deliberates and signs.”

Will there be a transition period? “If the end of the process suggests that all that’s required is detailed extra guidance, then there would be no need for a transition period. If we are saying that some new thing new has to be done, then our approach has always been that we will let the industry respond and adapt by means of a transitional period, but it’s too early to make that call.”

Last word

To Proair’s David McHugh: “One often hears people complain about change and new things coming like energy rating of buildings and how it is done. This is fine because people should complain if they think there is a better way. What many people tend to forget regarding changes in the building regulations is that a few short years ago there were no regulations at all. Now that we have them we can change them and hopefully improve the standard of our buildings as a result.”

- Articles

- Part L Building Regulations

- Venting opinions

- Ventilation

- airtightness

- proair

- heat recovery

- DEAP

Related items

-

Air tightness training course to launch in Carlow this March

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

Airtight delight

Airtight delight -

Partel’s airtight membranes now certified for passive house construction

Partel’s airtight membranes now certified for passive house construction -

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Mass timber masterwork

Mass timber masterwork -

Partel obtains EPDs for airtight membranes

Partel obtains EPDs for airtight membranes -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

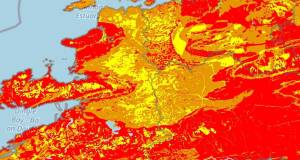

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

When is an A-rated home really A-rated?

When is an A-rated home really A-rated? -

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Manhattan modular apartments feature Wraptite membrane

Manhattan modular apartments feature Wraptite membrane