- Blogs

- Posted

Why we wrote Designing for the Climate Emergency

This article was originally published in issue 42 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

As it's title 'Designing for the Climate Emergency - A Guide for Architecture Students' explains, architects can help humanity step back from the void by integrating evidence-based sustainability approaches throughout their work. Co-authors Sofie Pelsmakers, Elizabeth Donovan and Aidan Hoggard shed some light on the thinking behind the new guide.

Designing for the Climate Emergency took us over two years to write. In that time, we saw the pandemic hit each country and climate-related records broken in different parts of the world: the hottest temperatures recorded, the longest heatwaves, the worst wildfires, extreme droughts in some parts and floods in others. We heard the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issue a Code Red: a severe warning that climate change is not distant. It is real, and it is already happening. We are in a climate emergency.

The urgency and scale of the transformation that is needed is unprecedented. This is because globally, we have been burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas at an incredible rate and scale. With every degree that global temperatures rise (it is already 1.1C globally, and we’re trying to limit that rise to 1.5C), we risk unhinging ecosystems further, leading to more extreme events and increased loss of lives, livelihoods, homes and cities, and devastation to the natural world. That is why each country is shifting towards a zero carbon or carbon neutral society. Because built environment processes are responsible for around 36 per cent of the CO2 emissions alone, carbon neutrality can only be achieved if we also stop using fossil fuels for the construction and operation of the buildings we design, and transform and start using the available resources we have responsibly on a global scale.

And it is not just CO2 that matters: every minute of the day, we use resources that can never again be replenished and that create waste, destroy natural and human habitats, and pollute the air, water and soil we rely on, jeopardising human life and wellbeing, and other species. Design choices we make at our ‘drawing boards’ affect people and communities thousands of miles away. For example, we import cheaper materials from regions halfway across the world and ignore the environmental and human costs of doing so.

Despite this awareness, almost every architecture project continues to contribute to the current climate crisis, embodied injustices and ecological breakdowns worldwide. Our architectural responses need to be drastically altered. Every single project needs to not only minimise but reverse these damaging processes immediately and create a positive and restorative impact – this is an essential part of a climate emergency design approach.

To do this, we must make an urgent shift in the values we hold, and a shift in how and why we do things. This is what our new publication aims for.

Our book, which is targeted at architecture students (which arguably includes each of us as teachers and practitioners too), aims to tackle the quadruple challenges of the climate emergency:

- Ensuring climate change mitigation (ensuring our actions don’t exacerbate the crisis further),

- Adapting to a changing climate (even if we stop burning fossil fuels today, we cannot escape the effects of a changing climate put in motion more than one hundred years ago),

- Creating positive and restorative designs (restoring prior damages inflicted),

- Improving climate justice locally and globally (no longer exploiting others – human, non-humans and nature).

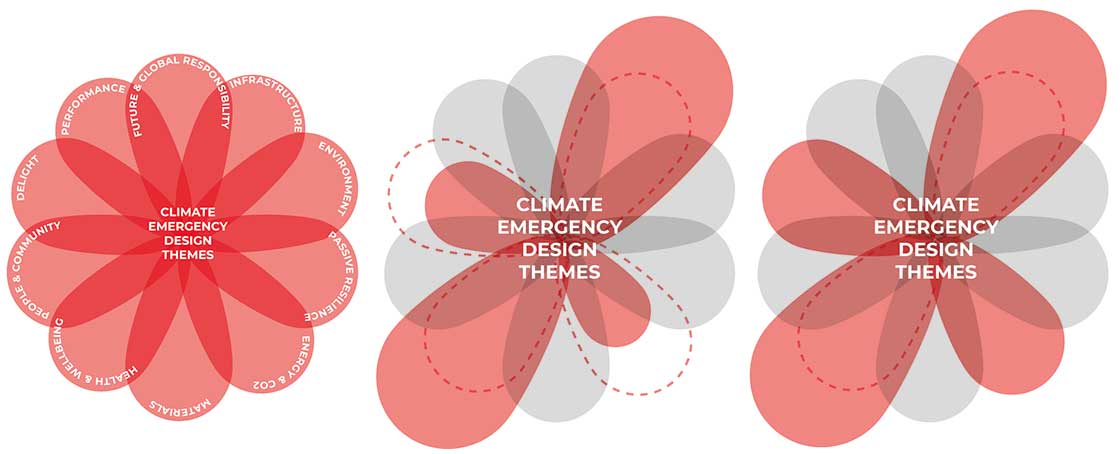

At the core of the book are ten climate emergency themes (see Figure 1), which are mapped against the UNSDGs and RIBA 2030 Sustainable Outcomes metrics, of which energy and CO2 is one theme. But our book goes beyond energy and CO2 solutions, ensuring that consistently high values in all areas of sustainable architecture are integrated into projects as part of a holistic approach to dealing with the climate emergency (see Figure 1). Often as architects we claim that our projects are sustainable, but they have rarely been holistically sustainable, tackling only certain aspects and neglecting others. By the end of studies, a student should be fluent in applying all themes in their design projects, as this is what is also necessary in practice.

Figure 1. The ten climate emergency themes in which high standards must be achieved (left image): future and global responsibility, infrastructure, environment, passive resilience, energy and CO2, materials, health and wellbeing, people and community, delight, and performance. The middle diagram indicates that to achieve holistic sustainable architecture, certain sustainability aspects cannot be prioritised (large red petals), at the expense of reduced standards elsewhere (the red dotted lines with smaller red petals). Instead, all aspects must meet high standards, even when some themes are prioritise.

While the book provides a wealth of information, it does not focus on simply providing more knowledge and more information. Instead, it focuses on the right questions that students should be asking and when; what information they need, and the actions and decisions they need to take at these different stages of the design process. To help students do this, there are around thirty key recommendation checklists to use throughout the design process and related to different climate emergency themes; a selection of two hundred listed case studies; a glossary and key notes to further explain the text. There are also around two hundred images, half of which illustrate student approaches from the UK, Denmark and Finland.

The book aims to instil sustainable values that go beyond the visible and calculable impacts of our own design decisions, and bring into focus the architects’ future and global responsibility. The future and global responsibility theme covers climate and social justice issues. The book also questions whether we should build at all, putting circular construction principles at its core (e.g., retrofit, adaptability, designing for disassembly) as well as future-proofing for a changing climate.

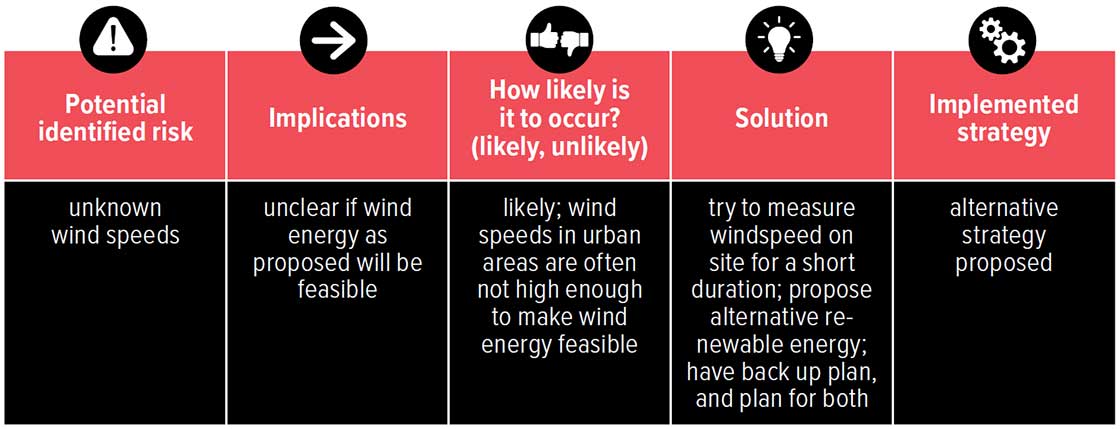

In architectural education it is important to emphasise that designing sustainable architecture and zero carbon buildings means little if this is only achieved on paper and if these standards are not met in reality, once the spaces are handed over to the users. As such, in the performance theme, we recommend that students create a ‘performance risk plan’ as part of their project to map out the project’s ‘risk areas’ (see Figure 2). By ‘performance’ we also do not simply refer to energy and CO2 (i.e., related to building and systems performance) but also to users’ well-being, satisfaction, and spatial and material performance.

Figure 2. Example of a ‘performance risk plan,’ which can be used as a template for understanding and reflecting on the potential risks within a project.

Our design decisions should be based on knowledge and the best available evidence, with foundations of how to achieve this provided in chapter one. However, we cannot claim our proposed designs are sustainable without evaluating if this is the case. While we cannot know for certain whether our designs work until they are built and used, we can do our best at the design stage to ‘test’ and ‘validate’ our designs. Validation means testing and checking if our project meets the sustainability goals we set in earlier design processes. In our book we focus on how students can set these goals early on, and a whole chapter is dedicated to validation and communication of these goals and approaches throughout the design process, illustrated with student examples.

Other themes also aim to shift the role of the architect and the role of architecture towards co-creating with others, and centring the needs of people and communities (including non-humans and nature, rather than centring ourselves or for recognition in outdated architecture awards. This is not to say that architectural contributions should not be delightful (delight is one of our ten core themes), but it is focused on the user and their experience.

As architects, we are co-creators and custodians of the built environment. We can – and must – be part of the radical change needed, and we must understand the impact of local decisions on the global scale. There is no room for error. Instead of seeing this as alarmist or an attack on our creative pursuits, it requires determination, conviction and optimism to trust that we are part of the solution, not the problem. And it requires us to reframe what architecture is, with more, not less, creative thinking. Our book is both a call to action for students and teachers to urgently reframe our values and culture as well as a tool to help achieve it.

Designing for the Climate Emergency - A Guide for Architecture Students, published by RIBA Publishing, is out now. Authors: Sofie Pelsmakers, Elizabeth Donovan, Aidan Hoggard & Urszula Kosminska