- Feature

- Posted

Developing story - Life inside Ireland's largest low energy housing scheme

Over the last decade, Cosgrave Developments have set about building a new neighbourhood near the south Dublin seaside town of Dún Laoghaire. Honey Park and Cualanor are two adjacent schemes comprising nearly 2,000 low energy homes, one of which houses this magazine’s editor, who has found a scheme with green credentials that go far beyond a good energy rating.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Buildings: 1,950-home sustainable neighbourhood

Completed: Work still in progress

Location: Dún Laoghaire, Co Dublin

Standard: A2 & A3 (BERs)

€620 per year (space heating & hot water —see ‘In detail’ for more)

In all the years I’ve been writing about low energy buildings, I’ve never had the chance to live in one. The stories we heard over the years from occupants of these buildings – about a palpable difference in comfort and anecdotal evidence of health improvements – in some way were abstract or theoretical to me when my lived reality was renting buildings that were either too cold or too stuffy, and invariably with a bit of mould thrown in too, exacerbated by the lack of outdoor drying options.

As serial renters, my wife Lauren and I had had a run of bad luck. We had lived quite happily and run the magazine for several years from a poorly built Celtic Tiger townhouse in Blackrock – complete with a 1 sqm backyard where you literally couldn’t stand a bicycle up on two wheels. Our first child, Rex, was born in 2013, and the house no longer met our growing needs. So we moved to a 1950s semi-d on Wainsfort Road, Terenure, where our daughter Sadie was born. This house was too remote from shops, given that neither Lauren nor I drive, and we had to move after a year when an electrician discovered the house’s electrics hadn’t been grounded and needed total rewiring. We hastily found a beautifully extended and renovated ex-corporation house on Kill Avenue, Dún Laoghaire that had been promised to us for three years.

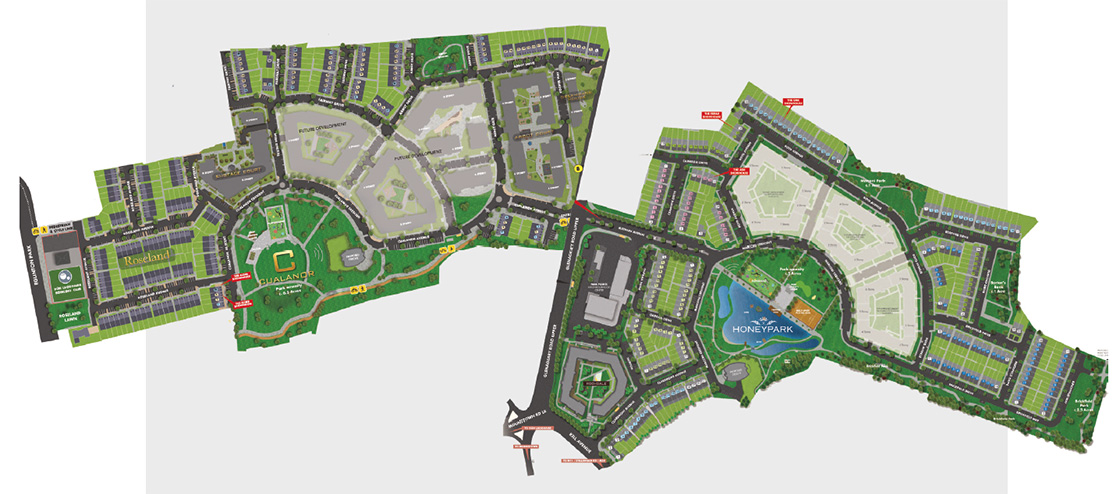

The two developments of Honey Park (top) and Cualanor (bottom) have a combined total of over 1,950 new homes, the vast majority of which have A2 BERs, as well as a 2,500 sqm shopping centre.

The two developments of Honey Park (top) and Cualanor (bottom) have a combined total of over 1,950 new homes, the vast majority of which have A2 BERs, as well as a 2,500 sqm shopping centre.

This article was originally published in issue 17 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

As lovely as this house – which had been upgraded to a B2 building energy rating (BER), but whose glassy extension made it prone to overheating – was, the transition upset Rex, who has since been diagnosed with autism. When the landlord changed plans and decided to sell up within our first year there, my wife and I were forced to look at our options. Working from home was becoming challenging – Rex and Sadie were prone to bursting into the office to play – so we decided to look for something smaller, and keep a separate office.

Lauren thought that we should look to stay in the area, to minimise disruption for Rex. As luck would have it, we found a new rental option in a development a vigorous stone’s throw away from our last house: Cosgrave Developments’ Honey Park.

It was close and familiar – Rex had even been to the playground and lake in Honey Park, and we regularly used the small shopping centre built by Cosgrave on the edge of the scheme. The energy performance struck a chord too – an A2 BER, high levels of insulation and decent airtightness, with heat recovery ventilation. So in May 2017 we moved into the Neptune building, a brand new 198 apartment building in Honey Park, secure in the knowledge that as this was a build-to-rent scheme, we’d have about as secure a tenure as is possible in the Irish private rental market. The company took out a little office on Patrick Street in Dún Laoghaire.

(top and bottom left) Both developments feature large parks and playgrounds, which help to create “a place that people want to live in”. Aside from retaining trees from the site where possible, mature plants are also added to help create a sense of place; (right) the impressive Honey Park playground provides a safe place for children to play and meet other kids from the area.

Honey Park sits on the site of what was once part of Dún Laoghaire Golf Club. Cosgraves bought that land in 2002, and developed plans to create two new developments: Honey Park and Cualanor, separated only by a road, which would ultimately consist of a combined total of over 1,950 new homes and a 2,500 sqm shopping centre.

While building a new golf club for Dún Laoghaire Golf Course in Enniskerry and a bowls club on the periphery of the Cualanor land, Cosgraves started the proverbial groundwork at Honey Park by building the park that would provide the scheme’s focal point, including a lake, a sizable playground, green areas, wildflower meadows and a basketball court.

I met developer Mick Cosgrave and consulting engineer Richard McElligott – in the local Costa coffee shop Cosgrave’s built, of course – to discuss the scheme’s quietly sustainable approach. Since starting out in 1979, Cosgrave Group have built 7,620 homes, in the process picking up countless awards and earning a reputation for quality.

Spectacular views from a roof terrace at the Leona building

I have to remember to check the weather on my phone in the morning.

Over the intervening 40 years, the company has developed what it refers to as the five pillars of excellence, which the company lists as quality (design, specification and construction); sustainability (energy efficient living); low maintenance (reliable, long term solutions); user focused design (homes for people to enjoy); and community benefit (a stage for living). These five pillars are made manifest in Honey Park and Cualanor, and a long-term view that was evident in the genesis of the schemes.

“The first thing we did was put in the park – five acres in that – before a house was built,” says Mick Cosgrave. “It’s a huge forward investment but it makes the place. You have to create a place that people want to live in.”

According to Cosgrave, aside from retaining trees from the site where possible, the group tends to put in mature plants to help create a sense of place. “So you arrive, it’s as if the house could have been there for five years. We’ve been doing that for the last 30 years.” “It’s more of a neighbourhood,” adds Richard McElligott.

Cosgrave explains that the lake went in for more practical reasons – storm water attenuation – but grew into an opportunity to provide amenity for residents while also supporting biodiversity. “We decided to make something more of it, working with [environmental NGO] the Curlew Trust. They gave us all [the advice] to create the habitats to attract the birds.” Sure enough, the lake is home to a cacophony of ducks, moorhens, the odd heron, and of course, the inevitable pigeons.

As someone who lives in Honey Park, I value having all of this nature on my doorstep, in a park with an impressive playground that people come from neighbouring towns to visit. Our two-bed apartment is 89.5 sqm, plus a balcony overlooking an internal courtyard.

Office pods at the Neptune building where part of this article was written

You have to create a place that people want to live in.

It’s sufficient for our needs, space-wise, but if cabin fever sets in we can take the kids outside in an instant to a place where they can burn off energy and have unstructured play with other kids. In our building there’s also a free gym and office pods – complete with Wi-Fi and coffee machine – where I regularly work, especially during magazine deadlines.

Walkable communities

Our office in Dún Laoghaire is a 15-minute walk away – a pleasant stroll through Honey Park’s sister scheme, Cualanor, taking in a forest trail with resident squirrels, and a walk past the playground in Cualanor’s own park. By happenstance or design, it’s more convenient for Cualanor residents to get to Dún Laoghaire on foot or bicycle than by car, thanks to pedestrian access at the rear of Cualanor, though the vast majority of residents still own cars, of course.

The sky gym in the Leona building.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are becoming a common sight in the two schemes, with several charge points installed in the underground car parks of the apartment buildings and high-speed chargers next to a GoCar car sharing club hub at the shopping centre. But a greener option than EVs is not to drive at all. My family are testament to the fact that it can be possible, easy, and – barring particularly inclement days – pleasant to get around by foot, whether it be for the daily grind of school and pre-school runs, shopping, work or weekend trips to the seaside, with frequent buses on our doorstep and trains only a brisk walk away.

It was this overall attention to sustainability that made such an impression on the judging panel, which I sat on, for this year’s Isover Awards, where two new phases at Cualanor – Fairway Drive & Abbot Drive – picked up the Excellence in Residential New Build award and Runner Up & Contractor of the Year award.

My fellow judge Pat Barry, CEO of the Irish Green Building Council, is effusive with praise: “This scheme exemplifies what creating sustainable communities is all about. We can’t tackle climate change with disconnected solutions. It won’t work if we build A-rated homes that still lock in high carbon lifestyles. We know we have succeeded in creating a great community when the low carbon choices are the obvious ones, when the most sensible and pleasant way of getting to the local shop, school or work is by walking and cycling, through a beautifully- designed biodiverse landscape. We know success when it makes more sense to be part of the local car club, saving the costs of car ownership for something more worthwhile like leisurely lunches in a local community restaurant or browsing the farmers market. The carbon transition will be less about technical solutions such as heat pumps and electric cars and more about the soft design skills that enable behaviour change.”

Energy use

But what about energy use? The vast majority of the 1,950 homes between Honey Park and Cualanor come in at A2 BERs, and our apartment is no different: an A2 rating with a primary energy score of 43 kWh/ m2/yr covering space heating, hot water, ventilation and lighting – a net total which would be reduced by a contribution to the ‘landlord’ areas (communal spaces like lobbies, hallways and stairs) by a centralised combined heat and power plant.

A pair of townhouses at Fairway Drive, Cualanor, one of the newest phases at the development

Since we moved in, we’ve used an average of 36.96 kWh/m2/yr at our heat meter, virtually entirely for hot water. In the 25 months that we’ve lived here, we’ve had perhaps one or at most two radiators on for about a week in total – and even then, sparingly. True, it’s a mid-floor, mid-block apartment, which gives it every advantage. But we live in a place that feels a lot like a passive house. It’s always warm – between 20 and 25C virtually all the time, though if memory serves it may have come close to 26C briefly last summer.

I value having all this nature on my doorstep

I have to remember to check the weather on my phone in the morning – otherwise I have no idea whether my kids are wrapped up too warm or not for the school walk until we’re out the door. It’s a disarming experience, and living in a building like this takes a bit of getting used to, so ingrained are your behaviours from living in uncomfortable buildings. It takes a while to remember you never need to put on jumpers or socks indoors.

The heat recovery ventilation also appears to be having a tangible, positive impact. My son has asthma, and his symptoms – which had been persistent up to that point – seemed to improve as soon as we moved in. Flare-ups tend to coincide with trips away – to his grandparent’s naturally ventilated Celtic Tiger bungalow, or an English Center Parcs holiday home in July where the air was thick with the residue of charcoal barbeques. But when we get back home, the coughing quickly subsides.

Mick Cosgrave is a strong advocate of heat recovery ventilation, the importance of which was impressed upon him following a trip in 2005 to the Passive House Institute in Darmstadt. “The heat recovery was the big thing for all this to work,” he said. “There’s no point in you insulating your house and having a hole in the wall.” Following that trip, Cosgrave installed heat recovery ventilation systems in all 280 apartments at Lansdowne Gate, a pioneering low energy scheme Cosgraves built in 2005. He had to go out on a limb to do so – the technology wasn’t mentioned in the 2002 edition of Technical Guidance Document F, the building regulations compliance document for ventilation systems. A senior official in the department’s housing section wasn’t keen, according to Cosgrave. “He wanted me to have heat recovery and put vents in the walls.” Thankfully Cosgrave managed to bring the department around.

Chris Halligan of Lindab, who provided the MVHR units throughout Honey Park and Cualanor, explains how the systems work: constantly supplying and extracting air at a low level, but boosted as required – either by an in-built humidity stat or a wired function triggered by the bathroom light coming on.

Mick Cosgrave of Cosgrave Developments.

“The integral humidity sensor increases speed in proportion to relative humidity levels, saving energy and reducing noise,” he says. “The sensor also reacts to small but rapid increases in humidity, even if the normal trigger threshold is not reached. This unique feature ensures adequate ventilation. The night time relative humidity setback feature suppresses nuisance tripping as humidity gradually increases with falling temperature.”

Summer bypass – where the ventilation system bypasses the heat exchanger – is operated by an internal damper when the external temperature is below the internal temperature, and the internal temperature is too high. “The bypass opens and allows the cooler outside air to help cool the dwelling,” says Halligan. The systems also feature evening and night-time purge modes, which again boost the ventilation rate when indoor temperatures are too high, though users can turn off the boost function.

From my personal experience, the seamlessness of the ventilation system’s operation has been a real boon: you just leave it alone, and it does its thing. “That’s one thing I learned from the Passive House Institute,” says Mick Cosgrave. “I asked them how do you control it? They said it’s very simple: you set it up, and it’s on. If somebody wants to open the window they open it, if it’s too warm. You don’t give people the option to [mess it up]. Keep it simple.”

Cosgrave speaks from experience: at Lansdowne Gate, where the developer was managing the rental properties before ultimately selling the scheme, user behaviour issues led to call backs over mould problems in a couple of the apartments. “The day you go in, everything is working, because they turned it back on. For the cost of running it, it’s something like 50c per day. These people were turning it off thinking they were saving money, and it’s the most dangerous thing they did because so little air was coming in.” Cosgrave learned from the experience. When we moved in to our apartment we were confronted by a sign next to the machine warning starkly never to turn it off, and Cosgraves provided a manual for the apartment, explaining how everything worked. Our system has worked well ever since, although it is overdue a filter change.

Combined heat and power

Heat recovery ventilation wasn’t the only innovative technology Cosgrave used at Lansdowne Gate: the 280 apartments were heated by a district heating system, with a centralised boiler house sending heat to each unit. Fresh from his trip to the Passive House Institute with services engineer Pat Dunphy, Cosgrave put in a system capable of delivering 7.5 kW of heat per unit for space heating and hot water, which post occupancy monitoring showed was overkill. “We ended up putting 10 modular boilers in when we could have done it with six,” says Cosgrave.

When Pat Dunphy retired towards the tail end of the Lansdowne Gate project, Cosgrave approached a number of the country’s best known M&E consultants about designing the heating systems for Honey Park.

“We gave them a budget of 7.5 kW per unit for the heat load on all the apartments and the houses. They came in at between 16 and 21 kW.” Why build in such redundancy? “It’s the engineer’s mantra of looking at it rather than looking for it,” says Richard McElligott, who came onboard with a much more streamlined approach. “As the blocks have come along here, we’ve tried to lower the installed capacity. So when we go and do a block of 150 or 160 apartments, we’re now putting in between 2.5 and 3 kW of capacity or less per unit.” It’s a major reduction, made possible by a more nuanced understanding of occupant behaviour, by the inherent efficiency of apartments – which have less external surface area for heat loss than other dwelling types – and the fact that Cosgrave’s insulation and airtightness specs are now approaching passive house levels.

Does that mean space heating demand has been close to eradicated? “Oh completely,” says McElligott. “During the day the trickle demand ambient load is very low. You basically get a spike in the morning – absolutely consistent as clockwork – for about an hour and a half every morning where it’ll jump up, and you get a similar one in the evening. Other than that it’s really, really low.”

The apartment buildings are heated by Buderus condensing gas boilers working in tandem with a bank of Dachs combined heat and power units, supplied by Glenergy, which cover about 40% of the heat load while providing electricity for landlord areas. While the renewable energy requirement in Part L is satisfied by solar PV arrays on the houses at Honey Park and Cualanor, the CHP units fulfil this role in the apartments, given that TGD L permits the use of CHP systems as an alternative means of satisfying the renewable energy requirement.

According to Fintan Lyons, managing director of Kaizen Energy, who manage the district heating systems in the various apartment buildings at the two schemes, the approach is meticulous: “During concept design each and every system is looked at in detail to see how improvements can be made to ensure the right equipment is sized and selected,” he says. “Our operational strategies are agreed and implemented during commissioning to ensure network return temperatures are optimized to 40 degrees or lower throughout the year. These low return temperatures allow the generation equipment – boilers and CHP – to operate in fully condensing mode, thereby maximising system efficiencies.

“All network pumps operate in variable speed based on the network [ie customer] demand. The CHPs operate 15 hours per day to power the landlord electrical services such as basement lighting and pumps. The CHP operation is optimised to off set expensive daytime electricity and delivers free heat into the heating system for residential customers so it’s a win-win for both the residential customer and management company.”

The net result? “The systems installed in Honey Park are amongst the most efficient district heating systems currently operating in the country,” says Lyons. “I am able to say this with confidence as we would operate the majority of the systems in the country.”

Before the recession hit, Cosgrave had plans to have a centralised plant room heating the entire development – plans that were ultimately dropped, and which fell out of favour when the apartment buildings were sold to different investors. The houses instead have individual Glow-worm gas boilers, with Cosgrave yet to be convinced about the long-term performance of heat pumps, in spite of their widespread uptake across the industry in Ireland in recent years.

The apartments are ventilated via Vent Axia heat recovery ventilation systems - which include prominent signs warning occupants not to switch the units off.

“In 20 years’ time, that boiler will still work,” he says. “And you’re not going to get a bill of five grand to replace it in ten years’ time.” Cosgrave swears by Glow-worm boilers in particular. “Glow-worm have an all-Ireland seven-hour replacement service on the [circuit] boards, and it costs €150 for a board that you can get anywhere. You go for any of the other brands which you’d say might be posher – you’d pay €500-600 for a board. It’s all to do with minimising the lifetime costs to the end user.” For similar reasons of reliability, Cosgrave opted for Danfoss hydraulic heat interface units for apartments, rather than more complex digital units.

How do the apartments perform in summer? Last year – which was one of the hottest summers on record in Ireland – some of our neighbours found it a little too warm, but our apartment held up well. Our main living space happens to be north-facing, but both bedrooms are south-facing, and the temperatures crept a little over 25C at times. The stairwell and corridors outside apartments do get warm at times. This may be due to high levels of glazing in the stairwell and heat loss from the centralised heating pipework – insulated pipework will still lose heat, due to the constant supply of hot water it holds.

That also means it can take a while running the tap before the water gets cold. Penthouses aside, many of the apartments are externally shaded by balconies, and all windows feature internal venetian blinds which – as a London Southbank monitoring study published in Issue 26 of Passive House Plus showed – can deliver relatively significant temperature drops. But Mick Cosgrave says overheating is an issue that the group is looking at – wrestling the structural implications and thermal bridging of external shading against the daylighting requirements that inform glazing ratios, etc.

In the overall context, these are fairly small quibbles. Ireland’s largest A-rated development to date – or A-rated neighbourhood, if you will – performs well in energy performance terms, but it succeeds on many other levels, and dispels the notion that being green involves sacrifice, self-denial and a decline in living standards. Honey Park and Cualanor are an important example of the benefits – the delight even – that sustainable places can bring. Places where people don’t have to waste precious time in traffic just to survive. Places with well-conceived public spaces that help engender a sense of community and encourage children to interact with each other and nature. Places that people would want to live in even if they couldn’t care less about the environment. Places that make it easy to be green.

Selected project details

Main contractor/developer: Cosgrave Group

Architects: McCrossan O’Rourke Manning

Structural engineers: DBFL

M&E engineer/energy consultant: McElligott Consulting Engineers Ltd.

Landscaping contractor: Carrig Landscapes

Airtightness testers: Greenbuild

Insulation/airtightness contractor: Usher Insulations

Heating contractor (apartments): Kaizen Energy

Prepaid heating system (apartments): Prepago

CHP: Glenergy

Condensing boilers (apartments & houses): C&F Quadrant

PV arrays (houses): Coolair

District heating consumer units (apartments): Danfoss

MVHR systems: Lindab

Airtightness membranes: Siga/Isover

Mineral wool insulation: Isover

PIR insulation: Xtratherm/Kingspan

Windows: Wright Window Systems

Roof windows (houses): Velux

Additional info

The following information relates to Charlotte and Leona apartment buildings (two adjacent blocks of apartments with 319 units in total), unless denoted (*) for whole Honey Park/ Cualanor scheme or otherwise stated.

Building type: 5/6 storey apartment blocks with circa 7 cores each. The units are each over a basement and constructed with masonry walls with an internal insulation liner.

Location*: Honey Park & Cualanor, Dún Laoghaire, Co Dublin

Budget: Construction costs are circa €70M for the two blocks

Space heating demand: Typically, less than 10 kWh/m2/yr, based on metered heat usage over the 12 months of operation less the hot water demand.

Energy performance coefficient (EPC): Averaging about 0.36

Carbon performance coefficient (CPC): Values including 0.331 (mid terrace house at Abbot Drive), 0.306 (mid floor apartment at Eustace Court) & 0.221 (apartment in Fairways building).

BER*: Majority of development A2 rated. Some ground and top floor units coming in at A3.

Airtightness: Generally, circa 1.5 m3/hr/m2 at 50 Pa. Thermal bridging: ACD default value of 0.08 used for DEAP calculations. However nearly all construction details were thermally modelled and if used for the apartments would deliver a thermal bridging factor of 0.06 on average. It has been noted that the gains in the DEAP programme are nominal at this level and only eff ect the losses associated with space heating which are working out at less than 30% of the thermal footprint of each unit.

Energy bills (measured)*: In the apartments in Honey Park & Cualanor the cost of heat energy for space heating & hot water, off the district heating system works out at circa €620 a year, covering the energy, standing charge, sinking fund and VAT costs per unit.

GROUND FLOOR

Apartment buildings: 700 mm thick podium flat slab with 120 mm PIR. U-value: 0.14 W/m2K

House floors: Strip foundations with 120mm

Xtratherm insulation. U-value: 0.11-0.13

Walls*: Brick outer leaf, cavity, block, internal 120 mm PIR board, service cavity and a plasterboard liner. U-value: 0.15-0.16 W/m2K.

Apartment roofs: Flat roof with PIR insulation over a concrete deck and a Paralon / Trocal liner. U-value: 0.16 W/m2K.

House roofs: Cold roofs with 300 mm of mineral wool insulation on the attic floor – cross laid to cover joists; on airtight membrane on plasterboard. U-values: 0.14 W/m2K.

Windows*: Thermally broken Kommerling C70 PVC frames with Diamond Glass double glazed units, with a 16 mm gap. U-value: 0.142 W/m2K. AMS triple glazed aluminium thermally broken system in penthouses.

Heating systems (apartment buildings): Centralised district heating system. 3 mini CHP engines are the lead heat source with a pair of boilers (duty/ assist). All gas fired. Ring main around the basement with a set of rising mains per core. Individual branch on each landing piped to a heat interface unit in each apartment. The heat interface units have heat meters and an instantaneous heat exchanger for hot water generation. The water is direct fed to the rads in the apartment.

Heating systems (houses): Glow-worm Flexicon modulating condensing gas boilers – typically 90.4% efficient, 18 to 20kW boilers. Ventilation*: Vent Axia Sentinel units throughout houses and apartments, with Kinetic Advanced units in Eustace, Charlotte and Leona, with an Appendix Q efficiency (2012) of 93% and 0.66 W/l/s.

Water: All water in apartments supplied off a central water tank and booster pump set which allows for better maintenance of the tanks and less energy used to pump the water. Low capacity cisterns used also.

MICROGENERATION

Apartments: Dachs CHP units generate electricity for landlord areas in apartments, while generating heat for district heating system.

Houses: Coolair 4 panel solar PV arrays – rising incrementally from an output of 225 to 300 Wp output per panel from the first phases at Honey Park to the last phase at Cualanor – meaning total outputs of 900 Wp to 1.2 kWp per house to cover background loads, with excess spilling into the grid

Image gallery

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/feature/developing-story-life-inside-ireland-s-largest-low-energy-housing-scheme#sigProId2b248af0d2