- Feature

- Posted

Hot topic

In spite of Ireland’s mild, temperate maritime climate, there is growing concern about the potential for overheating in residential buildings, highlighted by the current litigation in respect to overheating in the prestigious Lansdowne Place apartments in Ballsbridge, Dublin.

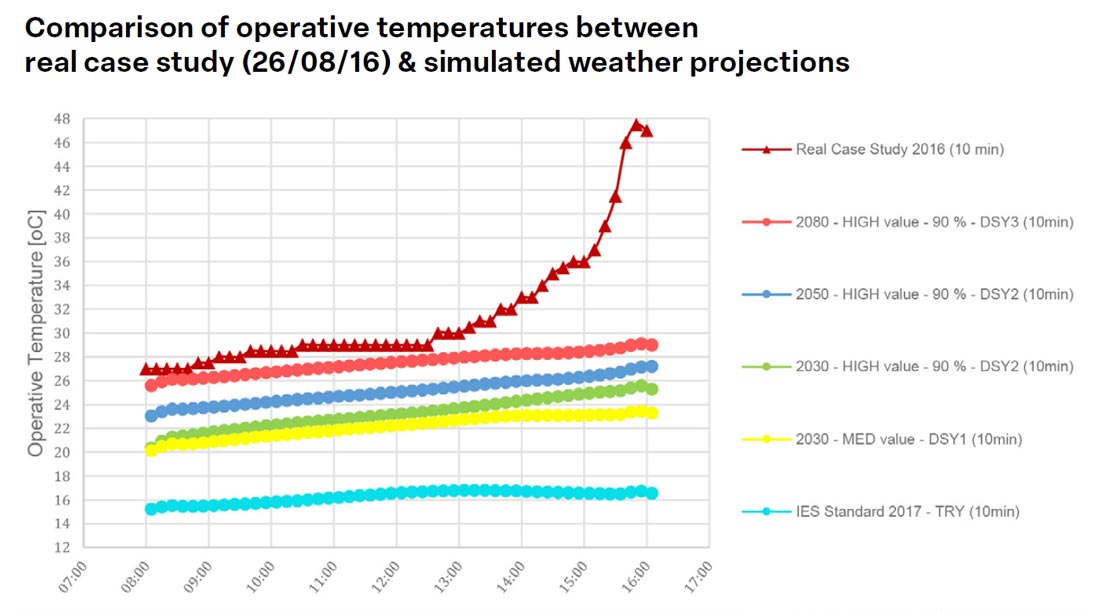

Severe overheating is not limited to low energy buildings, as the operative temperatures of 47.5C recorded in the Anello building in London demonstrate – a startling figure for an unoccupied, unheated building, albeit one with large, unshaded, southwest facing windows and single aspect rooms.

But it stands to reason that without careful design, overheating risks may be particularly acute in low energy buildings, given the emphasis on preventing heat loss. And although the passive house standard includes maximum temperature targets, some legitimate questions apply: are the targets right, and how do they compare to the targets set under Part L?

This article presents an overview of a post occupancy evaluation (POE) study of overheating in fifty residential units using three standards. This includes the monitoring results of indoor temperatures in thirty-seven Irish NZEB-compliant dwellings and thirteen rooms in an A3-rated student hall of residence. Twenty-four of the dwellings are certified to the passive house standard, as is the student building. Given that the student rooms are residential in nature, they’re considered as de facto dwellings for the purpose of this study.

Paradoxically, the results of the analysis, which was first published in a paper in the journal Energy and Buildings at the start of this year, are stark or reassuring, depending on how you frame them.

Reassuringly, the temperature profiles in all bar one of the thirty-seven certified passive house dwellings met the overheating target in PHPP. But starkly, a quarter of all fifty monitored dwellings failed to meet the targets set in TM59 , the Chartered Institute of Building Service Engineers (CIBSE) overheating standard referenced in Irish building regulations. (In defence of these projects, TM59 was not applicable when they were built).

This is unwelcome news for design professionals and clients alike, as there appears to be a lack of appreciation of the real risks of overheating and the need to assess if there is a risk of overheating when designing the building.

It is worth noting that the available data happens to centre on passive houses – as this task was made easier by the fact that passive houses require overheating assessments in PHPP (the Passive House Planning Package, the software used for passive house design). Excluding passive houses, only one of the properties was a new build NZEB, and overheating risk in NZEBs more generally is an area targeted for future research by the authors of the study.

There is a paucity of data in terms of overheating assessments for NZEBs. But as the aphorism goes, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. We can take reassurance in the case of Irish passive houses, that they are overwhelmingly meeting the overheating targets set in their design targets, even if in some cases they are not meeting more onerous targets they were not asked to meet at the time of design. We have little or no such evidence for NZEB homes, which should give us pause for thought.

However, in the past, passive house practitioners have typically used the PHPP to assess the potential for overheating. Based on the POE data this approach may be insufficient in the light of the new national regulations.

How is overheating defined?

This article was originally published in issue 47 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

In analysing overheating, it is important to specify which of the varying standards are being used to determine if there is a risk of overheating at design stage (using building simulation software) or actually taking place (based on a POE study). If a building, based on empirical evidence, is shown to be exceeding time-related temperature targets, can we necessarily say it fails to meet those targets?

What if the observed outdoor temperatures are higher for more time in a given year than may have been assumed in the overheating standard, meaning a building is facing longer or more intense heatwaves than anticipated in the design? What if there are more occupants in the building than allowed for in the design, meaning more heat gain from body heat, appliance use, more frequent bathing, etc? Or what if the occupant is not using the building as intended in the design, for instance by turning on space heating on warm days, by turning off summer bypass mode on ventilation systems, or by not manually managing natural ventilation and shading strategies? Can we say in such cases that a building is failing to meet the overheating targets set in building regulations or voluntary standards such as passive house?

How do we distinguish cases where the problems are not to do with the design, or with any failings of the modelling assumptions that informed the design, from cases where it is clear that the model failed to identify serious overheating risks in the design? As this study assessed overheating against the targets set in three standards, it is important to clarify what those standards require.

Passive house

In terms of building simulation, while the Passive House Institute has a very clear definition for overheating, this is based on the set air temperature threshold of 25C and a whole building analysis, rather than a roomby- room analysis.

TM59

This contrasts with TM59, which looks at two elements, both of which must be met:

TM59

Criteria A – an adaptive temperature threshold, which makes allowance for high external temperatures, and the period over which high temperatures are experienced, and carries out the adaptive analysis based on individual rooms, rather than the “one zone” analysis inherent in the whole building approach.

Criteria B – a set bedroom air temperature threshold of 26C.

WHO

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends avoiding temperatures in excess of 24C as it can have negative health impacts.

What analysis was done to determine overheating extent?

Temperature data was recorded in fifty dwellings (twenty-seven new build and twenty-three retrofit) at five-minute intervals in a mixture of rural, town and urban settings. The thirty-seven passive house units (which included twenty- four NZEBs, and thirteen student rooms) comprised twenty-six new build and eleven retrofit projects. The new builds included nine homes in housing schemes, four individual homes and the thirteen aforementioned student rooms, while the retrofits comprise eleven social housing apartments for the elderly. The observed overheating was determined based on the three objective overheating standards – CIBSE TM59, passive house and WHO temperature thresholds. In addition, the rigorous POE study incorporated occupant satisfaction surveys (OSS) and interviews, to examine and understand end user perspectives and potential drivers for overheating.

It is important to note that the requirement to conduct a TM59 analysis was not in place at the time of construction of the buildings in this study. However, the new dwellings complied with the current NZEB standard, and so provide valuable insights into the performance of Ireland’s current low energy dwellings standard.

How did the passive house units perform?

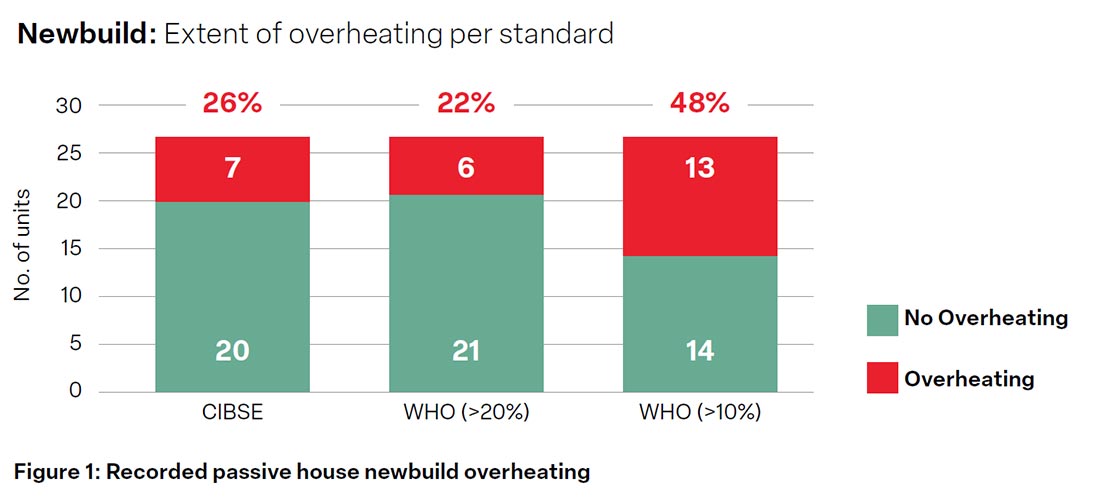

When assessed against TM59, 26 per cent of passive houses overheated (Fig 1), whereas only one (i.e. 3 per cent) failed the passive house criteria (when mitigating factors are included).

Moreover, average temperatures in 48 per cent of the new build passive house residences exceeded the WHO-recommended interior temperatures for more than 10 per cent of the year, and 23 per cent for more than 20 per cent of the year.

While the occupant satisfaction survey (OSS) indicated broad alignment between the occupant’s perspective and the CIBSE and WHO standards, significantly more occupants were dissatisfied with overheating than was indicated by the passive house criteria.

Different overheating standards – different results

In a number of schemes, window safety restrictors impeded the ability of occupants to appropriately control the ventilation of their residences.

The disparity between the overheating results emanating from the three standards was a significant finding. Residences are significantly more likely to fail TM59 than the passive house criteria, but the reverse can also happen: one of the 3-bed scheme passive houses failed the passive house overheating standard, but passed TM59. (In this case, while the overall temperature – which was derived from the mean of the living room, kitchen and bedroom temperatures – exceeded 25C for 10 per cent of the year, meaning it failed the passive house test. Meanwhile the bedroom was under the TM59 criteria 1B threshold of 26C, and the temperatures in the bedroom, living room and kitchen did not exceed the TM59 criteria 1A for adaptive thermal comfort).

There are a number of reasons for the different results, with a principal one being that different static temperature thresholds are used: WHO uses 24C, passive house uses 25C and TM59 criteria B uses 26C in the bedrooms. In addition, TM59 criteria A uses an adaptive threshold which changes based on prevailing outside temperatures. Note that failing either criteria A or B means that the dwelling fails to meet CIBSE TM59. Key in the disparity is also the ‘room-byroom’ analysis of overheating potential inherent within the CIBSE and WHO standards compared to the building-wide criteria of the passive house analysis. The principal reason for failing TM59 was the 26C static temperature threshold in the bedroom. The TM59 analysis of the performance of individual rooms is much more demanding than the passive house criteria which treats the dwelling as a whole, and allows the temperature threshold of 25C to be exceeded for up to 10 per cent of the year – i.e. for more than five weeks of the year.

Other key findings include the lack of control some occupants had at their disposal to regulate high temperatures. For example, there was little evidence of external shading and, in a number of schemes, window safety restrictors impeded the ability of occupants to appropriately control the ventilation of their residences.

Interestingly there was also disparity based on the subjective assessment perspective captured by the OSS. For example, the same residence was considered too warm by one occupant yet very comfortable by the other.

Finally, a significant finding was that some overheating (as defined in the objective standards) was being caused by poorly installed / commissioned heat pump-based heating systems and occupants requiring high interior temperatures. When allowances are made for these mitigating factors, overheating instances reduced in the retrofit analysis to 5 per cent – meaning only one of the overall sample of 23 NZEB retrofits was overheating.

Recorded versus predicted overheating

The only way of knowing if overheating is actually taking place is to measure it via a structured POE study. For the sample presented here, building surveys took place and a structured OSS (such as the internationally recognised building use study (BUS) methodology) was carried out in order to gain further insights. Measurements included temperature, relative humidity and CO2 in the living room, kitchen and main bedroom, and also temperature and relative humidity were measured outside the building.

Based on the data gathered via this POE approach, analysis of overheating was possible based on the three independent overheating standards.

It is noted that, when the passive house criteria and TM59 overheating criteria are used, it is typically in building simulation software to reduce the risk of overheating in advance of construction rather than assess if overheating is taking place after construction via recorded data. The research paper provides valuable insights into how buildings actually perform based on recorded data, rather than simulated data.

Need for POE

The research highlights the need for accurate post occupancy evaluation to be carried out on buildings to ensure that lessons are learned now in order to avoid embedding problems such as overheating in our future building stock. How will we know if there is a problem unless we measure it?

The results clearly indicate that relying exclusively on the passive house overheating standard may result in residential buildings failing the TM59 requirements.

For practitioners, it is therefore important that the promised overheating assessment methodology is added to DEAP to enable overheating risk to be assessed as per TGD L, and that TM59 analysis is carried out if a risk of overheating is identified. Meeting the targets set out in PHPP may help keep overheating to reasonable levels, but it may not be sufficient to meet TM59.

Conclusion

Overall, the analysis shows that there can be an issue with overheating in Irish NZEB compliant homes.

Based on the monitoring results there is an urgent need to implement measures to guard against overheating early in the design stage in Irish dwellings and educate industry in the associated design and systems implications.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland under Grant Agreement 18/RDD/358 and Grant Agreement RDD744 in conjunction with Ulster University via the Innovation Voucher scheme, Wexford County Council, and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown architects office. It would also not have been possible without the generous support and time allocated by the occupants of the houses.

The author

Dr Shane Colclough is Research Fellow at UCD with a special interest in post occupancy evaluation of buildings. In addition to his research work and being principle at the consultancy firm Energy Expertise Limited, Shane is a board member and former chairperson of the Passive House Association of Ireland.