- Case Studies

- Posted

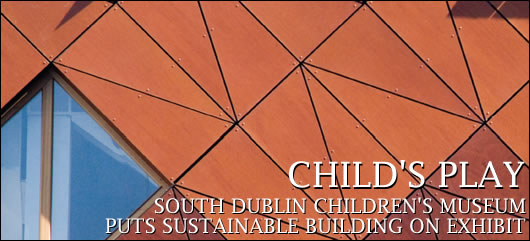

Child's Play

Imaginosity, the new children's museum building in Sandyford's Beacon South Quarter development, is getting the Austrian eco-house treatment, combining low energy, modular construction with a plethora of low carbon energy technologies. Jason Walsh visited the site to take a look.

A e5.5 million building located in Sandyford is taking shape. Tightly packed onto a small site, the new children's museum is being developed for Landmark Developments by ÖkoHaus, an Irish company with a central European heritage.

Named 'Imaginosity', the children's museum is one of the key developments in the new Beacon South quarter district, a mixed-use area in the Dublin suburb of Sandyford. With conceptual design by architectural practice Traynor O'Toole, the project architects are O'Keefe and Associates, an emerging eco-aware firm.

At 1,800 sq. metres the children's museum is a landmark development and a central part of the strategy to develop Beacon South Quarter as a genuinely mixed area, not just a dormitory adjunct to a collection of industrial estates and business parks.

ÖkoHaus, pronounced 'Oeko house', an Irish firm with an Austrian partner manufacturing wall panels to its specification, has taken on the task of building the museum and in doing so have applied their characteristic construction methods and concern for energy efficiency to the project.

Home-grown in Austria and Ireland

Despite its work on the children's museum, ÖkoHaus is probably best known for its work on high-specification residential buildings: "We do about 12-15 high spec one-off houses a year, all in the upper market," says ÖkoHaus's Josef Steiner.

Unlike other companies in the prefab market such as Griffner Coillte, ÖkoHaus does not at present offer design 'packages'. Instead each house is uniquely designed based on ÖkoHaus's system which can be adjusted as is necessary.

The houses are timber frame buildings, designed to achieve significant energy savings such as, for example, an average annual space heating requirement cut of around 40 per cent.

"About half of our turnover is commercial, the other half residential," says Steiner.

As a company ÖkoHaus is keen on using as many natural materials as possible, for example, insulation, where possible: "Rock wool is our standard, we [also] do hemp insulation," says Steiner.

According to Steiner energy use is a major motivating factor in clients deciding to have their homes built by the firm: "Energy efficiency is a big part of it. In Austria all of our partner's houses have the blower air test and here we do it if the client requires it," he says.

Additionally plans are underway for a testing facility in Ireland: "In Galway we're developing a test house with which we want to achieve an A1 rating," says Steiner.

Natural ventilation: the strategy is to not use any mechanical ventilation systems, instead relying on designing to optimise natural air flow and air-tightness

As a result of its Austrian heritage Ökohaus's dwellings are all air-tight: "It's a basic requirement, to get grant aid in Austria, to produce an energy certificate."

Clearly these benefits are beginning to appeal to Irish house-buyers: "The [Irish] market is receptive," he says. "There are a huge amount of inquiries."

Apart from energy efficiency, the ÖkoHaus methodology brings the benefit of rapidity to the construction process: "If you consider everything is produced off-site - all of the panels - the only thing we do on-site is close the corners and add the ceilings," says Steiner, explaining that the ceilings are not installed in the factory in order to leave space for a service conduit. "In a typical house you're talking [about] 5-6 days to assemble the superstructure."

The prefabrication process also brings with it the efficiency of factory engineering: "The element of control in the process is essential. Every house built in the traditional [blockwork, on-site] method is a prototype. In factory-built construction the cut is always the same. You can address issues and the people are trained - the quality control is much better," he says. "In traditional houses there's a lot more risk. It's hard to check things."

It's not a view that is without merit. Traditional construction methods are coming under increasing pressure not only in terms of energy efficiency or quality control but even as an anachronistic throwback to pre-industrial times.

The view from the museum's roof across rapidly developing Sandyford. The external wood cladding can be seen in the foreground and to the left is the upper area of structural glazing

The glass, supplied by Austrian manufacturer Katzbeck, is double glazed, argon filled and features a whole unit u-value of 1.1

Writing in his foreword to the book 'Why is construction so backward?' Martin Pawley noted a British newspaper has begun to publish a property supplement packed with information - and advertising - regarding construction, saying: "Only one aspect of the new supplement slipped a gear and betrayed its wish-fulfilling obsolescence and that was its name - Bricks and Mortar - a term as antique as it is universally understood. A term that, on its own, explains why the building industry will not match the = productivity of the motor industry until it is radically reformed, and the pages of every building supplement start to carry headlines like 'Inside the new Tartan 306', or 'Autohouse ships 200,000 modulars in record year'."

Modular musings

All of the ideas, motivations and, most importantly strategies, behind ÖkoHaus's residential buildings have found their way into the Children's Museum. Nevertheless, the scale of the projects does make for some differences, notably the input of external subcontractors: "The main thing with a commercial building is to maintain the advantage from start to finish, it's a learning curve for subcontractors," says Steiner. "On our own houses we tend to minimise external input - just mechanical and electrical engineering."

Despite the factory-built and modular nature of the construction system the Children's Museum is subject to many of the same pressures as any building site: "We're exposed to the same difficulties that any main contractor would face."

ÖkoHaus's Josef Steiner explains his company's building methods

Building on its Austrian experience, Ökohaus stands by its buildings: "In Austria there is a 30 year liability on the contractor for hidden faults," explains Steiner. "People are forward-thinking in terms of [questions like] 'what problems is this going to create for me in five years, in ten years time?'"

Construction began on-site in October 2006 and is due for completion and handover in June 2007.

Unlike ÖkoHaus's residential builds, the museum is not a timber frame construction: "The superstructure is a steel frame - because of the size we couldn't use timber," says Steiner. At four storeys, if the decision had been to use timber frame, the museum would have been amongst the taller timber frame building's built in Ireland, although leading ecological architecture practice Leech Gaia's Navan Credit Union, at five storeys-and complete with timber lift shaft-points to the greater heights that low impact building can reach.

View of the children's museum's front and side elevations showing its unique structural glazing, both attractive to the eye and relatively energy efficient

The building is clad externally with Parklex, phenolic panel with a double-sided timber veneer: "They're installed vertically," he says. "They're insulated with 240 millimetres of rock wool insulation and a UV-resistant breathable membrane." This is standard in ÖkoHaus's residential developments, the only significant difference being that the insulation is more usually 200mm.

Attention has been paid to getting the most out of the building's glazing in terms of energy efficiency. The glass, supplied by Austrian manufacturer Katzbeck, is double glazed, argon filled and features a u-value of 1.1: "This is for the whole unit," says Steiner, "not just the [centre] pane."

The building's structural glass elements, meanwhile, were supplied by Pilkington and achieve a u-value of 1.3.

Overall u-values for the rest of the building are equally impressive: the walls have a u-value of 0.17, the floor is 0.14 and the roof is 0.17.

The roofing materials are copper and a bitumen moving membrane for the flat element and the ceiling vaults make use of a high density polystyrene insulation

"The whole concept of the building is [one of] natural ventilation," says Steiner. Indeed, the building features thirty louvres that lead into a ventilation cavity while the sun heats the building's façade, creating a chimney effect to circulate air. "It was quite a process to get it right," he says. "The aim is to cool without a mechanical system."

"A building like this can't be 100 per cent air-tight," says Steiner, "because there are a lot of elements and there are [strict] fire regulations but all of the components are built to the same standard as in our residential buildings."

The building's sustainability efforts extend beyond energy efficiency into energy generation, through a combination of a gas-fired micro combined heat and power plant and air-to-water heat pumps with a backup gas boiler, though Steiner does not anticipate the boiler being used.

The building even seems to be bursting with eco gadgets, as there are also Viessmann vaccum tube solar panels and Windside wind turbines located on the roof. However, as Paul Tighe of M & E consultants Ethos Engineering told Construct Ireland, the breadth of the range of technologies employed was more to do with educating the children coming to the museum than simply achieving the most efficient, cost effective result.

Approaching the museum (above left): despite a very tight site, the prefabrication process has resulted in a rapid build; from below (above middle): cladding being added into place; a wall unit (above right) in progress on the roof. Dupont Tyvek membrane is used to prevent the ingress of wind-driven rain

Steiner is nonetheless confident that the building's overall performance will be superior - and not only because of good insulation and a natural ventilation strategy: "The combined heat and power plant is very efficient," he says.

Indeed, clichés about Teutonic efficiency aside, it appears that the whole project, including the construction process, has been developed with efficiency in mind. If ÖkoHaus's work on the museum is anything to go by, bricks and mortar - or rather, blocks and mortar - may find themselves becoming passé or even déclassé, replaced by a manufacturing process that stresses efficiency in both construction time and energy performance.

l

Selected project team members:

Client: Landmark Developments

Conceptual architect: Traynor O'Toole

Project architect: O'Keefe & Associates

Main contractor: ÖkoHaus

M & E engineers: Ethos Engineering

Mechanical contractor: Leo Lynch & company

Micro CHP: Kinviro

Solar panels & heat pumps: Precision Heating

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Child's Play

- imaginosity

- sandyford

- Eco House

- modular

- ÖkoHaus

- natural ventilation

- Viessmann

- Parklex

Related items

-

Proctor creates head of global sales for modular offsite sector

Proctor creates head of global sales for modular offsite sector -

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Low carbon, cement free carbon rooms being built in Cork

Low carbon, cement free carbon rooms being built in Cork -

Lidan completes modular buildings for local authorities

Lidan completes modular buildings for local authorities -

Lidan win National Enterprise Award

Lidan win National Enterprise Award -

Offsite and modular: The future of construction

Offsite and modular: The future of construction -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on -

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub -

Viessmann boilers keeping visitors warm at revamped Postal Museum

Viessmann boilers keeping visitors warm at revamped Postal Museum