- New build

- Posted

Award-winning passive house makes elegant mark on the South Downs

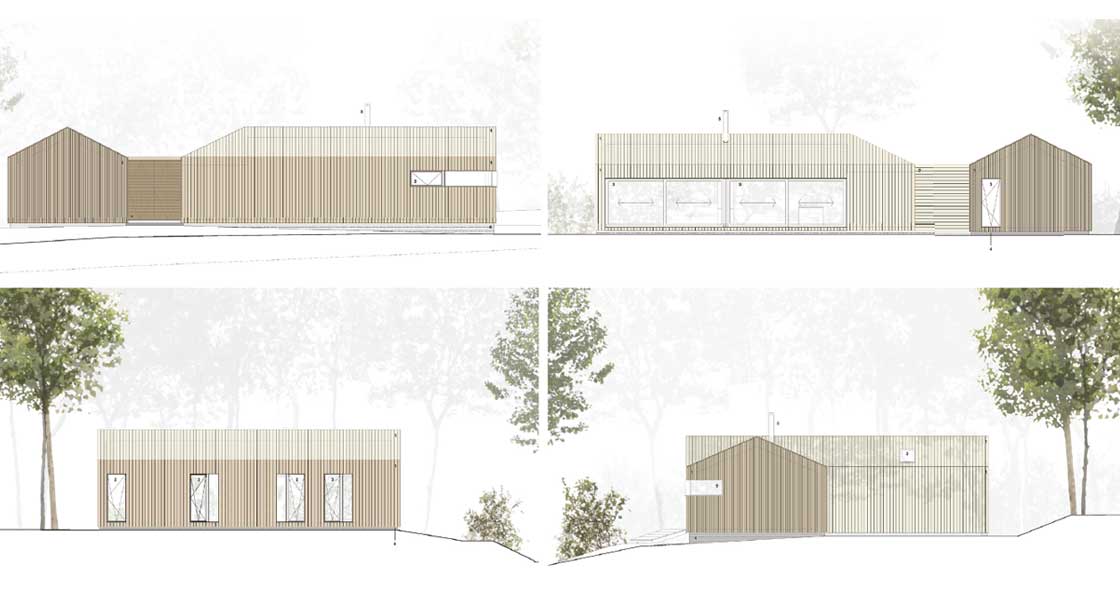

Despite the challenges of getting planning permission within a national park, a new passive house on a hillside in the South Downs managed to woo the planners with a sympathetic, discerning design inspired by a surprising source — two dilapidated old chicken sheds.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Energy bills £21 per month for space heating

Building: 119 m2 detached passive house

Build method: Structural insulated panels (SIPs)

Site & location: Semi-rural site, Lewes, East Sussex

Standard: Passive house classic certified

The architect Charles Meloy – who has built the first passive house in the Sussex Downs National Park (SDNP) – dreamed for “decades” of building an affordable, sustainable house in this beautiful landscape. But not only was it prohibitively expensive, there were also restrictions on the types of developments allowed. Active searches for a suitable, economical plot proved futile. Then, one day back in 2013, Charles was relaxing on a walk across the Sussex Downs with a friend when his imagination was fired by a pair of disused chicken sheds a few minutes’ walk from Lewes.

“We used to do a walk on an ancient drove road used by fisher folk to carry fresh fish from Brighton to the county town of Lewes. I wouldn’t be much of a developer as it was actually the third time I’d walked past the site before I noticed two dilapidated chicken sheds in a garden,” he says. “It suddenly struck me that we could build a house on the land and design it in a way that carried echoes of the original sheds.”

Charles quickly entered into a conversation with the owner who used the sheds for storage. He struck up a provisional verbal agreement to buy the land that was later formalised. The sale for a pre-determined price was conditional on Charles receiving planning permission on the site, which is outside of the Lewes town boundary but within the national park.

This article was originally published in issue 35 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Despite this challenge, Charles was confident of getting planning permission when he filled in his application in 2014.

“We had a lot of things going for us. The use of the land was residential as we were eff ectively building on a section of their garden. Another plus was that the existing buildings were still there, and they were dilapidated, so we could prove that a new structure would lead to an ‘enhancement and promotion’ of the use of the national park, which is one of the key criteria for planning. We placed Sussex bullock hedging right along the roadside to blend into the surrounding landscape and we used untreated western red cedar that weathers over time and blends in beautifully with the surrounding woodlands,” he says.

Charles took care to get all his future neighbours on side. He met the owners of the three houses that are adjacent to the site and explained his plans. Everyone reacted enthusiastically. Charles then showed his design to the local conservation group Friends of Lewes, who were equally supportive. “I think when you prepare a planning application, it’s about being neighbourly and polite. If you don’t take the time to explain everything to all the stakeholders, the danger is that when they get the planning letter, it comes as a shock. An unexpected planning letter can land as heavy as a lump of lead when it comes through their door.”

A lot of the support was inspired by his elegant and sympathetic design. The essence of his concept was that the two new singlestorey buildings would carry a memory of the original chicken sheds. The two sheds had covered an area of 100 m2, whereas the completed house, which also utilises the gap between the sheds, is 125 m2. Charles was fortunate in that the original L-shaped layout, although not ideal from a heat loss perspective due to the large surface area, allowed for the living and sleeping areas to be split, with the open plan living area having a southerly aspect to benefit from solar gain in winter.

The first shed was replaced with an open-plan space with living room and kitchen. Meanwhile, the second ‘shed’ with the bedrooms was fitted with east-facing windows that provide morning light. In between, Charles designed a linking section for the service core, “We didn’t have to fight the existing form one bit. Open plan areas can be sprawling, but the detachment of the two sections gave us some definition,” he says.

Charles was committed to building a passive house, but not at the cost of the aesthetics. He was adamant that the architectural design had to come first. “That might not be music to some passive house designers, but it was an attempt to see if there really were any restrictions implied by the design when aiming for [the passive house standard]. If there were, they had to be integrated into a coherent piece of architecture,” he says.

His imagination was fired by a pair of disused chicken sheds.

Prioritising the architecture set additional challenges for the passive house consultant Dan Gibbons, founder of Ape Architecture & Design in London. Charles and Dan have known each other since they shared a flat as students of architecture in Edinburgh and have a good rapport.

“It was satisfying working with Charles from an architectural point of view. With a lot of passive houses I’ve worked in, the project has been driven by what makes sense for PHPP [the passive house design software], whereas Charles emphasised the design. It meant I had to up my game to come up with solutions to offset some of the more compromised areas,” Dan says. “And it stands up as a very architectural passive house, whereas a lot of them can look a bit lumpen and unfinessed. More often than not it becomes more about the best performance quality than whether it looks good.”

One complicating factor was that Charles wanted to express the ground floor slab on the outside of the building for aesthetic reasons, whereas a more common method for a passive house would be to insulate the ground slab externally.

“It made it harder to achieve [the passive standard], but for Charles it was a line in the sand,” Dan says. “We had a lot of discussions and spent a lot of time going back and forth working out the details. We had to work around having an exposed structural slab on the side of the building, then an insulated screed internally, while making sure we could still get the structural connection between the slab and the SIP (structural insulated panel) frame without there being a detrimental thermal bridge. But we managed it and it meant we got a very clear line aesthetically on the outside of building where you can see the concrete slab before the timber starts.”

Dan recalled having “lots of amusing discussions” about the window designs. “Charles initially wanted to finish off the timber frames at the window reveals which relied on some large pieces of aluminium framing,” he says.” But this would have created a large thermal bridge that sucked heat out of the building.

“We had to do some careful modelling to make sure the aluminium was not directly connected to the windows. We also had lots of discussions about the window suppliers as when we were running the PHPP numbers and considering the windows Charles wanted, we always had to take into account his budget. After a few alterations, we eventually found a supplier with the performance we needed for the price he was willing to pay.”

Budgetary considerations were behind Charles’ decision to use SIP panels for the frame. SIPs are essentially a ‘sandwich’ of insulation, often polyurethane foam but in this case EPS, between two structural boards like OSB. Charles wanted the structure above ground to be lightweight to offset all the heavy elements touching the ground, including the concrete internal flooring and the exposed concrete at the base outside.

Timber frame was considered, but the SIP option was more economical and the suppliers were able to install them quickly. For Dan, it was the first time he had worked on a passive house using SIP frames. “My preference would still be for timber frame with natural insulation, but the SIP panels made it easy to achieve the blanket U-values we needed from the walls by insulating correctly,” he says.

To manage costs, Charles took charge of almost the entire build. He continued to work four days a week for his Brightonbased practice Meloy Architects, but in the evenings, he drove down to the site and often didn’t stop work until midnight. The fifth day of each working week was devoted to his self-build, as was one day every weekend. At times, he was helped out by a friend he had met years earlier on a bus trip in Australia, and who was training to be a teacher in Lewes.

Charles wanted to express the ground floor slab on the outside of the building.

Together, they installed all the insulation in the floor and added the cladding on the outside of the house. They also did the stud work, took care of the plaster boarding and fitted the internal doors. “It was tiring, but I had no option but to keep going until I’d finished. I worked out we used 10,000 screws for the cladding outside. But you actually get pretty efficient after you’ve done 1,000 or so!”

Charles employed sub-contractors for specialist jobs, such as the groundwork, fitting the SIP frame, the windows and the concrete flooring. Sub-contractors also helped out with the bathroom and the cabinetry. “The build went smoothly. It was the opposite of one of those Grand Design style TV programmes where everything keeps going wrong!”

With Charles doing most of the work a huge amount of money was saved, and Hill House cost a very reasonable £250,000 to construct (not including the cost of the land). Last year, it won four separate RIBA awards — in the south east, sustainability and small project categories, as well as a national award.

1 The ground floor concrete slab was left exposed on the outside of the building for aesthetic reasons; 2 erection of the SIPS frame underway;1 The ground floor concrete slab was left exposed on the outside of the building for aesthetic reasons; 2 erection of the SIPS frame underway;3 210 mm Xtratherm Thin-R insulation covers the floor; 4 laid on top of this is a 110 mm screed; 5 Intello airtightness membranes and taping onwalls and pitched roof; 6 this is followed inside by more Xtratherm Thin-R insulation on walls and roof, and then 25 mm timber studs formingservices cavity on walls; 7 after that, there is further layer of OSB inside; 8 architect Charles Meloy with his wife Hannah and their children onthe site; 9 Western red cedar external cladding on walls and roof.

Everything has been designed exactly as we want, and everything works as planned.

Despite the focus on design, the passive house standard was achieved comfortably, and the building offers exceptional thermal performance and airtightness.

Hot water is generated with an air source heat pump and extra space heating can be provided through a sealed wood burning stove.

Charles lives with his wife and three small children at the property, which is near to the village of Kingston and a 10-minute walk into Lewes. Sat on the top of a breezy hill which was once home to Lewes’ windmills, it’s in the countryside, but near schools and amenities.

“It’s a huge change from the very tall, tight townhouse we had before in Brighton, and we love it. Everything has been designed exactly as we want, and everything works as planned,” he says.

Selected project details

Architect: Meloy Architects

Passive house consultant: Ape Architecture & Design

Mechanical and electrical consultant: Alan Clarke

Structural consultant: Reaction Engineers

Passive house certification: MEAD Consulting

Planning consultant: Pro Planning

Arboriculturalist / ecologist: PJC Consultancy

Daylighting assessment: DeltaGreen

Foundations: SMD Formwork

Steelwork: South Coast Steel

Windows and doors: Doorstop Southwest Ltd

Roof lights: Solar Vision Ltd

MVHR: Systemair

Heat pump: Ariston

Airtightness testing: Tophouse Assessments

Build system: SIPS Eco

Additional wall & roof insulation: Xtratherm

Thermal breaks: Armadillo Plates

Airtightness products: Ecomerchant & Ty-Mawr Lime Ltd

Underfloor heating: Heat Mat, via BTR Tech

External blinds: Hella

Roofing: DMB Flat Roofing Ltd

Electrical: John Wadham

Plastering: Rafferty (Plasterers) Ltd

Landscaping: Worman Construction

Ironmongery / doors: Aspex

Concrete flooring: Steysons Granolithic

Cedar cladding: Wenban Smith

Sanitaryware: CP Hart

Wood-burning stove: Westfire

LED Lighting: Lightfoot LED

Permeable paving: Tuff Turf

Wastewater treatment system: Klargester Biodisc

Cabinetry / kitchen: JM Furniture

In detail

Building type: 120 m2 SIPs passive house

Location: Lewes, East Sussex

Completion date: Jan 2017

Budget: £250,000

Passive house certification: Passive house classic certified

Space heating demand (PHPP): 13 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 12 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 110 kWh/m2/yr

Primary energy renewable (PHPP): 51 kWh/m2/yr

Hot water demand (PHPP): 17.2 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 4.38

Overheating (PHPP): 0% of year above 25C

Number of occupants: 4

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.6 air changes per hour

Energy performance certificate (EPC): B 89 Thermal bridging: Critical thermal bridges, slab edges, steel beams, window frames etc were modelled in Therm – establishing an average Psi value of 0.012. All remaining thermal bridges were left as the PHPP default of 0.01 even though sample modelling of the standard SIPs details suggested that lower Psi values were being achieved.

Energy bills (measured or estimated): Based on final energy demand figures in PHPP, USwitch.com suggests a lowest available annual space heating bill of £248, or £20.66 per month, and hot water bill of £259, or £21.58 per month. Figures include VAT but not standing charges. Space heating figures do not include the wood burning stove, for which all wood so far has come from the site.

Ground floor: 110 mm screed over 210 mm Xtratherm Thin-R insulation over 200 mm concrete slab. U-value: 0.101 W/m2K

Walls: Western red cedar external cladding on battens and counter battens, followed inside by Tyvek UV Facade breather membrane, structural insulated panel comprising 172 mm SIPS Eco EPS insulation sandwiched between 11 mm OSB boards, Intello air tightness membrane, 60 mm Xtratherm Thin-R insulation, 25 mm timber studs forming services cavity, 11 mm OSB, plasterboard. U-value: 0.108 W/m2K.

Pitched roof: Western red cedar external cladding on battens and counter battens, followed inside by roof deck, Tyvek UV Facade breather membrane, SIPS Eco Structural insulated panel comprising 172 mm EPS insulation sandwiched between 11 mm OSB boards, Intello air tightness membrane, 80 mm Xtratherm Thin-R, plasterboard. U-value: 0.108 W/m2K.

Flat roof: Single ply membrane, followed beneath by 18 mm plywood to falls, 120 mm Xtratherm Thin-R, 18 mm plywood, 50 mm Xtratherm Thin-R between joists, ventilated cavity followed underneath Intello air tightness membrane, plasterboard. U-value: 0.123 W/m2K.

Windows & external doors: HON Quadrant Studio FB IV-9 timber-aluminium windows and doors. Typical spec: 44 mm triple glazing with Saint-Gobain ClimaPlus Ultra N glass & a Swiss spacer bar. Ug value: 0.50 W/m2K, dB value: 34, average overall U-Value: 0.80 W/m2K.

Roof windows: Vitral 4-degree Skyvision Comfort triple glazed Ecoline openable rooflights & Vitral 4 Skyvision Ecoline frame-only fixed rooflights. Ecoline glass, 32 mm low-e, krypton fill. Ug = 0.7 W/m²K.

Heating system: Ariston Nuos 250i heat pump for domestic hot water and also supplying duct heater in MVHR system, plus underfloor heating if needed in extreme weather. Westfire 35 standalone wood burning stove.

Ventilation: Systemair VTC 200 MVHR system. Passive House Institute certified heat recovery rate of 90%.

Image gallery

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/new-build/pecking-order-award-winning-passive-house-makes-an-elegant-mark-on-the-south-downs#sigProId77dac9416b