- Upgrade

- Posted

History repeating

Through passion, patience, and architectural expertise, a 16th century Carmel-ite friar’s cottage in Kinsale, owned by Passive House Plus columnist Dr Marc Ó Riain, has achieved what many thought impossible— an A1 energy rating for a Tudor-era building. But not without challenges.

Click here for project overview

Development type: 102 m2 house, built in the 16th century with multiple wall types

Method: House renovated in stages over 20 years, settling on natural insulation, heat pump, and 12 Longi Solar PV panels

Location: Kinsale, Co. Cork

Standard: A1 BER

Space heating and hot water cost: €163 per month total energy costs including standing charges and VAT – including charging an EV for over 30,000 km/yr worth of driving. See In detail panel for a full breakdown.

Executing an energy upgrade to an older building naturally requires a more thought-out and considered strategy to overcome idiosyncrasies and issues that might not be found in more modern homes.

For buildings with a distinct architectural heritage (with or without listed status), there’s also the job of balancing the demands of architectural conversation with the desire to shrink carbon footprints.

Take another deep retrofit: an 18th century farmhouse in Clane, Co Kildare, featured in Passive House Plus back in 2016 that had just achieved an impressive-for-the-time BER of A3. While adding a modern extension and applying a fabric-first approach along with a clever heat pump system, the owners spoke of several challenges they endured in satisfying the demands of the local authority to preserve as much of the original building as possible.

But in 2025, does the expertise and knowledge now available for the sympathetic energy retrofitting of older buildings mean that such projects are no longer quite the challenge they used to be?

The recent awarding of the top A1 BER score to a 16th century former friar’s cottage once associated with a Carmelite Abbey would seem to suggest so, but the seductive simplicity of that score conceals a 20-year journey – with a lot of learning along the way. What’s also true is that the owners’ 20- year journey to this point still has further to go, but as things stand, it’s by some way the oldest A1 retrofit in the country.

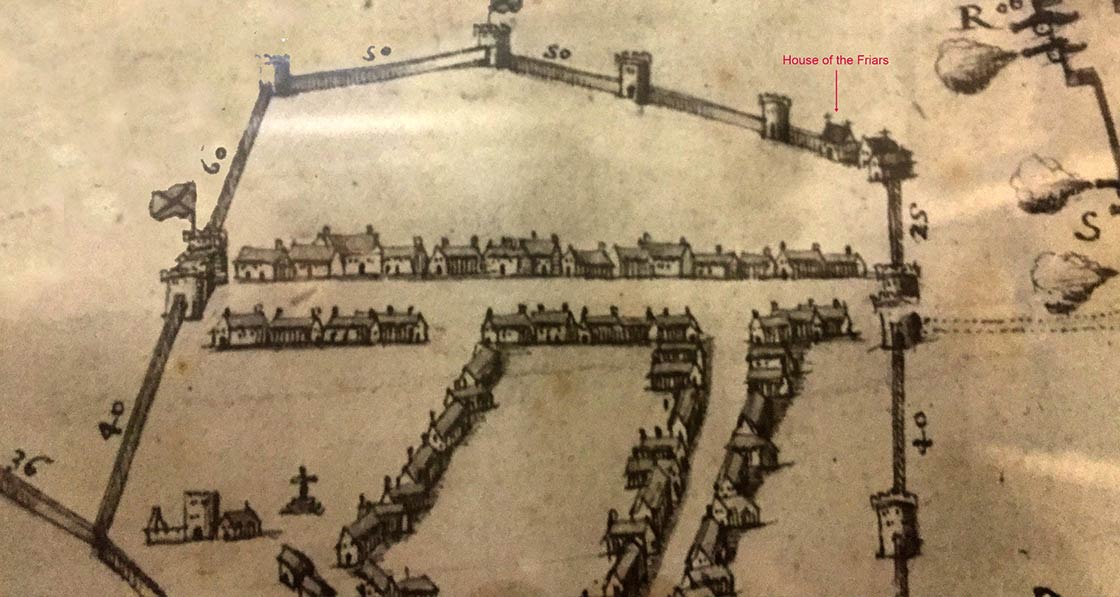

The original building’s story can be traced back to around 1560, when local records show it was one of a number of properties in Kinsale that made up the Carmelite friary, called St Mary’s Abbey, which included a church, belfry, hall, some friar houses, and a cemetery. When the Carmelite Order was suppressed in 1541 following the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII, a number of the friar’s houses were disbursed, and Abbey House was first sold in 1560 to a local merchant named Robert Meade, according to a historical record of the sale.

The siege of Kinsale in 1601 saw all the abbey buildings destroyed except for the two cottages outside the abbey’s walls—including Abbey House.

This article was originally published in issue 50 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

These cottages were basic structures: four stone walls, a fireplace, and a simple loft bedroom in the eaves, but by 2003, when Dr Marc Ó Riain – who, fittingly, authors a long-running column for Passive House Plus on the history of low energy building design – bought Abbey House, it had undergone a number of 'renovations'. The first was after the 1960s when it was condemned by the local council but later rescued by a local builder. At that time, the rear stone wall was pushed back by about 1.2 metres. This was followed in the mid-eighties by a dormer first-floor extension and then shortly after by a side extension with a toilet and kitchen built using single leaf hollow blockwork.

It becomes clear that despite the undoubted historical provenance of the cottage, these alterations probably sabotaged any prospect of it being certified as a listed building. Even so, Ó Riain reckons the local council didn’t bother to list any building that was built outside the walls of the abbey, not even those cottages that remained fully intact. Any listed statuses were reserved for buildings located closer to the town. Ó Riain met his wife, Deborah, shortly after buying the house and together they set about their energy upgrade project in a number of phases starting in 2005.

As the couple behind Rua Architects, which specialises in energy retrofits, remodelling and extensions for older buildings, they have several design and architectural qualifications between them, including passive house design and Marc’s PhD in zero energy retrofitting. But Deborah is also a registered conservation architect, and together the couple have led retrofit projects of several properties more than one hundred years old.

Having said that, the extent of the work that was needed to right the wrongs of previous so-called ‘renovations’ became clear early on. The floors were bitumen-covered with terracotta tiles laid directly on earth, with no insulation. The original stone walls were left exposed in parts, while other areas were clad in woodchip panelling.

Retrofitting is rarely about reaching a perfect endpoint. Rather, it’s about guiding a building towards better health, performance, and longevity, while respecting its story.

“The electrics were highly unsafe, with 1930s two-core telephone wire that ran from sockets behind woodchip wallpaper to wallmounted sconces, and you could physically feel the heat from the wires through the wallpaper,” Ó Riain said. “How it hadn’t burned down is still a mystery to me.”

Though it had been vacant for some three years, the good news was that the building remained dry and free from serious damp or mould issues. So, while it was undoubtedly tired, it still offered a solid base for a renewal.

After a lot of careful thought and research, the first upgrade in 2005 focused on the ground floor, and included replacing the single glazed windows at the north-facing rear and side with new Vrøgum double glazed timber units. A new kitchen door opened onto an external timber deck.

The old concrete floor was removed and replaced with 50 mm of PIR insulation beneath a 120 mm concrete slab, but without a traditional DPC (damp proof course), and finished with parquet flooring—reclaimed from an abbey in Scotland—which Ó Riain says was chosen for its breathability and stability against residual damp. They also fitted cork edging at the external wall perimeters to allow subfloor moisture to escape.

The ground floor walls were battened and internally insulated with 80 mm PIR-backed plasterboard, while passive wall vents were fitted. A bespoke timber front door was commissioned, and any existing front windows and doors were resealed. A BER assessment in 2010 brought the building up from F to C2.

The second phase of this retrofit took place in 2015, but not before Ó Riain began his PhD and started learning more about passive house design. An early practical application of this knowledge came in the form of a thermal heat loss calculation he had to do as part of a retrofit grant application to the SEAI to satisfy them that not insulating part of the thick stone walls on the inside of the cottage’s original footprint was acceptable because it only accounted for about 15 per cent of all the walls in the property.

By 2015, having both completed passive house design training as well as becoming members of the lecturing team at the Cork Institute of Technology (now Munster Technological University), the couple began the second phase of the retrofit by turning their attention to the first floor, where pitched ceilings in all bedrooms were stripped of latting and plasterboard and upgraded with PIR boards between the rafters, but still with a 50 mm ventilation gap.

An airtightness membrane was carefully taped at all junctions, and a 50 mm insulated plasterboard layer was cross-fixed beneath the rafters before being skimmed. The loft received a further 300 mm of blown Ecocel cellulose insulation on top of the existing 120 mm between the rafters. The walls of the 1980s extension were internally insulated with Gutex Thermaroom breathable woodfibre insulation. A high-efficiency 87 per cent rated stove was installed in the sitting room to replace the back boiler.

Overall, this phase went well, resulting in a significantly improved thermal performance and the property being given a BER B3 rating at that point.

Then in 2020, they invested in new slimline casement windows with an Ovolo profile from Brendan Hunter of Hunter Joinery in Tipperary, thereby preserving the building’s character.

Phase four took place during 2023, when the Ó Riain’s took the opportunity to replace the end-of-life oil boiler with a heat pump. Although the home’s fabric has been improved with insulation in most areas and some airtightness works, Ó Riain says that the house wasn’t designed for the kind of low temperature heating that would enable a heat pump to operate at full efficiency. In large part this is down to the compromises that historic buildings can pose – not just in terms of limiting fabric ambitions, but heating emitters too. The house already had “really nice modern heritage looking rads – not cast iron” all of which were kept, bar one which had rusted. Two radiators were added into the system for larger rooms. “All you have to do is find radiators which give you the wattage”, says Ó Riain, who decries the aesthetic impacts that modern steel radiators can have on old buildings.

The plumber had set up the system as what he described as “semi-pressurised” with a couple of vertical steel rads upstairs, but Ó Riain found that upstairs wasn’t getting warm enough. He puts it down to the pressure being too low on a long heating circuit, and stratification occurring in the tall radiators. “With hindsight I’d go with lower rads, and a fully pressurised system,” he says.

As the house doesn’t have enough radiator area to allow low temperature heat to be trickled in consistently, the heat pump is faced with a bit of a challenge. The unit the Ó Riain’s picked —a Thermia Itec Eco 8— is required to deliver heat at 55 degrees and returns it at 45 degrees, meaning a sacrifice in terms of efficiencies. According to Ó Riain, despite this the performance is good enough that for every €1 of electricity it uses, they get €2.50 worth of heating energy.

They also took the opportunity to install 5 kW of solar panels and an EV car charger. With these accumulated measures, the BER was bumped to its current A1 rating, making Abbey House by some way the oldest known A1 retrofit in the country. Looking at the house through the sharper prism of passive house design principles, Ó Riain admits that air quality is the one area where it falls down.

“We don't have mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR), and it's the one thing I wish we did have, because we've got two dogs and you're opening the window to ventilate the space, but then the benefit of the heat pump is getting hit by doing that. But I remember my problem, going back to my first passive house training over in Germany, was thinking that the Irish people would never accept a house with windows closed all the time… I don't think my wife still accepts it, so therefore I look at these older buildings in a different way.

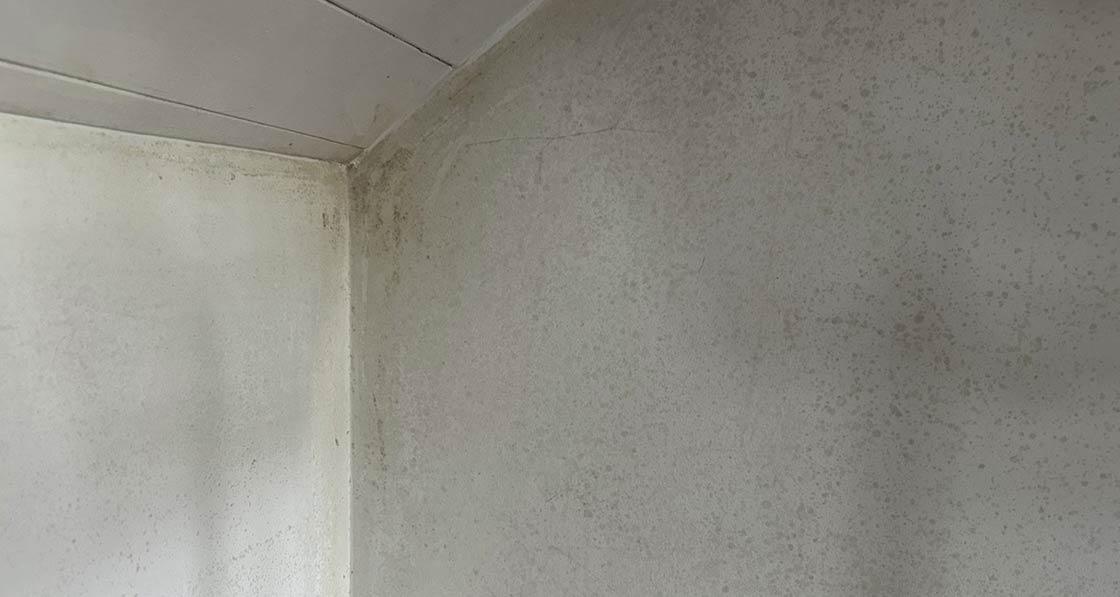

“We've done work at different stages because that's what we could afford at the time, but we did go into it with a strategy of passive actions first, active measures last. So, we’ve benefited, but we've done things that don't neatly fit into the passive house theory of a building. We put in a wood burning stove and my wife loves it. She sits on top of it. And in the kind of old building that we have, with its beautiful character, it still works. It doesn't take away from the building at all.” When Ó Riain first spoke to Passive House Plus about the project, he was honest enough to report that the couple were experiencing a minor mould issue on a northeast facing bedroom wall that they believed was down to their decision in 2005 to internally insulate the walls of the hollow block extension with insulated plasterboard.

Awareness of this particular insulation strategy and its propensity to generate interstitial condensation is now more widespread these days, thanks in part to Joseph Little's seminal ‘Breaking the Mould’ series of articles that was published in the progenitor to this magazine, Construct Ireland, back in the early noughties – a series that has been credited as prompting the creation of a national code of practice for retrofit, SR54.

However, Ó Riain later investigated further by cutting a 300 mm hole in the plasterboard and found it was bone dry behind with no sign of mould. So, it’s clearly just surface mould in a spot that’s not getting quite enough ventilation, which he believes is partly down to a poorly performing radiator on the other side of the room.

The couple haven’t yet decided how to fix it, but one option is to eventually upgrade the internal wall insulation to the Gutex woodfibre board like they’ve used in other rooms (and which are among the warmest rooms in the house). If anything, the issue probably underlines the value of using materials that allow moisture-laden air to move through the fabric of older buildings. Indeed, another future measure that is being done with improved breathability in mind is the front façade, where they plan to hack off the sand and cement render that was likely applied sometime in the last 90 years and replace it with an insulated cork lime render.

-

Existing single glazed windows which came with the house

Existing single glazed windows which came with the house

Existing single glazed windows which came with the house

Existing single glazed windows which came with the house

-

New Hunter Joinery slimline casement windows fitted in 2020.

New Hunter Joinery slimline casement windows fitted in 2020.

New Hunter Joinery slimline casement windows fitted in 2020.

New Hunter Joinery slimline casement windows fitted in 2020.

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/upgrade/history-repeating#sigProId1dac99bf5d

This is because the uninsulated stone wall is still losing some heat and some of the exterior timbers are rotting either through exposure or being unable to breathe or dry out properly.

To quote some of Ó Riain’s own words regarding his retrofit journey: “Retrofitting is rarely about reaching a perfect endpoint. Rather it’s about guiding a building towards better health, performance, and longevity, while respecting its story. As a practice, we’ve learned to embrace the evolving nature of old buildings, integrating modern materials and technologies while keeping their character intact.”

-

In 2015 the couple removed the timber latting or plasterboard from the pitched roof, to insulate and airtighten the roof;

In 2015 the couple removed the timber latting or plasterboard from the pitched roof, to insulate and airtighten the roof;

In 2015 the couple removed the timber latting or plasterboard from the pitched roof, to insulate and airtighten the roof;

In 2015 the couple removed the timber latting or plasterboard from the pitched roof, to insulate and airtighten the roof;

-

50 mm PIR on slope, airtight layer to all surfaces and 50 mm insulated plasterboard to inside face of pitch and ceiling

50 mm PIR on slope, airtight layer to all surfaces and 50 mm insulated plasterboard to inside face of pitch and ceiling

50 mm PIR on slope, airtight layer to all surfaces and 50 mm insulated plasterboard to inside face of pitch and ceiling

50 mm PIR on slope, airtight layer to all surfaces and 50 mm insulated plasterboard to inside face of pitch and ceiling

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/upgrade/history-repeating#sigProId5a0ace54e9

So, if this particular retrofit journey is set to continue, what’s the next chapter? An MVHR system is under consideration, but Ó Riain admits it might be challenging to install in relation to space, noise and duct routing.

But even with MVHR, he concedes the house would be unlikely to achieve passive house certification due to challenges in getting airtightness to the requisite levels, especially as parts of the original building don’t have a proper foundation.

“I don't see why we should do it. It’s a really old building which we really like, it's got great character, and it’s now running fairly efficiently— not as efficient as a passive house, but fairly efficient. I plug my EV into it, and it's making twice the amount of electricity that I need today at the beginning of April. I think we need to look at this old stock that we have and be sensible with it.”

-

The house in 2010 with open fire

The house in 2010 with open fire

The house in 2010 with open fire

The house in 2010 with open fire

-

A room sealed stove installed in 2015

A room sealed stove installed in 2015

A room sealed stove installed in 2015

A room sealed stove installed in 2015

-

The outdoor unit of the Thermia Itec Eco heat pump, installed in 2023

The outdoor unit of the Thermia Itec Eco heat pump, installed in 2023

The outdoor unit of the Thermia Itec Eco heat pump, installed in 2023

The outdoor unit of the Thermia Itec Eco heat pump, installed in 2023

-

The house's electricity demand is substantially reduced by PV arrays to the front and rear.

The house's electricity demand is substantially reduced by PV arrays to the front and rear.

The house's electricity demand is substantially reduced by PV arrays to the front and rear.

The house's electricity demand is substantially reduced by PV arrays to the front and rear.

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/upgrade/history-repeating#sigProId949f6a4747

Project overview

Ireland’s oldest A1-rated dwelling, restored over 20 years in a step-by-step process by RUA Architects. The house which has been recorded as being first sold in 1560 is an old Friar’s cottage inside the walls of Kinsale town. It’s a typical stone construction original cottage with a 1980s extension in hollow block with the original attic converted into a dormer.

Building type: Stone construction, no foundation, earth floor, no DPM, standing on a shale base, likely constructed in the 1500s or earlier. It’s a three-bedroom two-storey house with multiple wall construction types and 1,100 sq ft. It achieved a B3 rating in 2012 and an A1 rating in 2023. Site type & location: Urban site, Abbey Lane, Kinsale, Co Cork.

Completion date: November 2023

Budget: €100,000 over 20 years (not including site purchase and professional fees)

Passive house certification: N/A

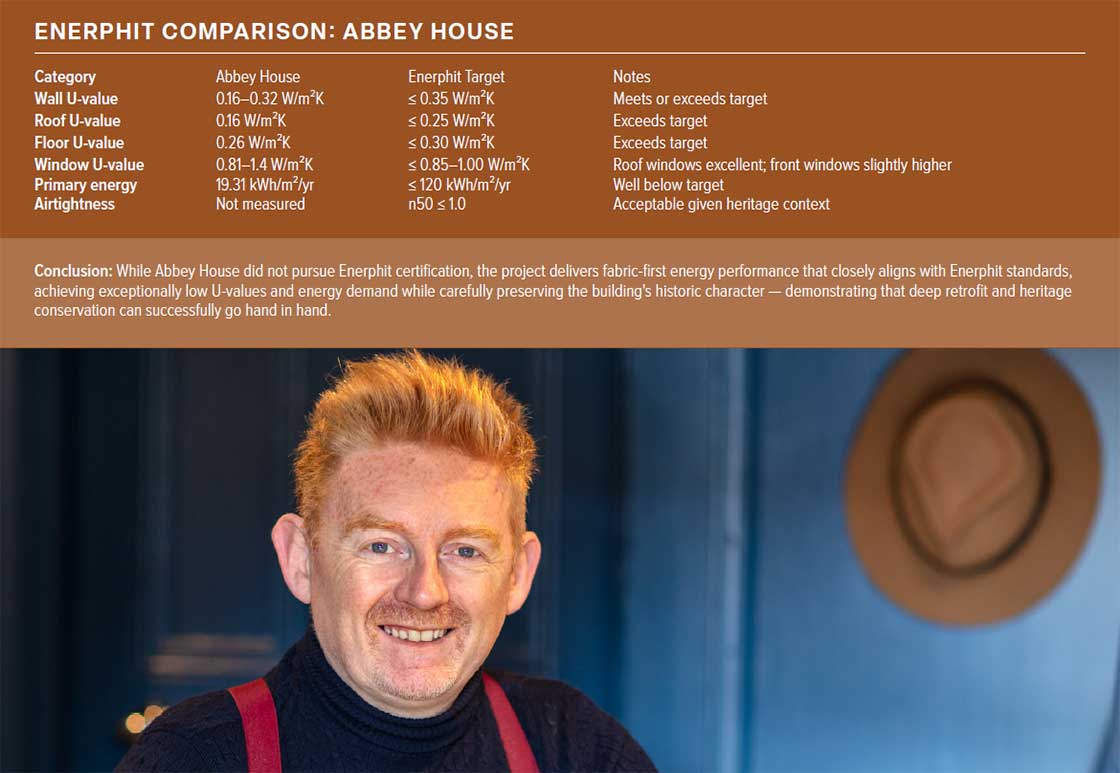

BER: Originally: 2002 Pre BER; Before: B3 (139 kWh/m2/yr) (mid retrofit); After: A1 BER (23.9 kWh/m2/yr)

Primary energy non-renewable (PHPP): After: 70 kWh/m2/yr

Primary energy renewable (PHPP): Before: N/A; After: 51 kWh/m2/yr

Net primary energy: 19.31 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor: 1.97

Embodied carbon: Not conducted

Measured energy consumption: Before: 111 kWh/m2/yr (Jan-Dec 2020, figure based on electricity bills & excluding electric car charging). After: 55.5 kWh/m2/yr (Feb 24-Jan 2025, figure based on electricity bills & including electric car charging).

Energy bills: Before: €1,200 on home heating oil (2019), ICE car fuel cost €3,069/a, €2,217 electricity/a at €0.18c/ kw (2019). After: €1,960 on electricity for all-electric house, including standing charges (Mar 24 – Feb 25), including electric car charging €1,681/a (5,141kW/a), net balance excluding car €279 per annum for house only.

Airtightness: Not tested

Ground floor: Before: Uninsulated concrete floor. U-value: 0.5 W/m2K. After: (50 mm PIR, with 0.022 W/mK thermal conductivity. U-Value: 0.26 W/m2K.

Original house walls: Before: 600 mm stone wall with 20 mm sand & cement plaster. U-value: 2.1 W/m²K. After: 100 mm Gutex Thermaroom internal insulation. U-value: 0.32 W/m²K. Some of the existing stone walls on the ground floor remain exposed.

Extension walls: Before: 200 mm hollow block concrete wall with 20 mm of exterior sand and cement plaster, a 25 mm air gap internally with timber studs (25x50 mm at 600 mm centres) and a 12.5 mm plasterboard internally. U-value: 1.82 W/m²K. After: 82.5 mm / 90 mm phenolic internal insulation on treated baton. U-value: 0.16 & 0.21 W/m2K.

Roof: Before: Sloped with no insulation. Roof slates to sloped areas. 100 mm mineral wool insulation on the flat between roof joists (30 m2) and a combination of plasterboard ceiling internally and timber latting. U-value: 1.82 W/m²K. After: 300 mm Ecocel blown insulation in the cold attic space 0.13W/m2k. 50 mm PIR between roof joists, Pro Clima Intello Plus intelligent airtight membrane, 50 mm cross joist phe-nolic insulation. 0.19W/m2K. Area-weighted roof average U-value: 0.16W/m2K.

Windows & doors : Before: Single glazed, timber windows and doors. Overall approximate U-value: 3.50 W/m2K.

New double-glazed windows rear: Windows and patio door Vrøgum double glazed timber. Overall U-value of 1.26 W/m2K.

New double-glazed windows front: Timber windows with SlimGlaze argon filled double glazing. Overall U-value of 1.4W/m2K.

2 roof windows: Fakro U6 thermally broken triple glazed roof windows with thermally broken timber frames. Overall U-value: 0.81 W/m2K

Heating system: Before: 20-year-old oil boiler & radiators throughout entire building. After: Thermia Itec 8 kW with sCOP of 4.45 fitted existing steel traditional column radiators from Best Heating.

Ventilation: Before: No ventilation system. Reliant on infiltration, chimney and opening of windows for air changes. After: The house uses a natural ventilation system with humidity-controlled Aereco wall inlets that automat-ically adjust airflow based on indoor humidity levels to optimise air quality and energy efficiency.

Electricity: 12 x Longi Solar LR5-54HPB-405M panels solar photovoltaic array with average annual output of 4.46 kW. No storage, prioritised for domestic hot water heating using an Eddy via immersion and electric car charging, excess electricity exported.

Sustainable materials: Reclaimed timber parquet from an abbey in Scotland, supplied by O’Flynn Flooring, is sustainable because it preserves historic materials, reduces demand for virgin timber, and lowers the embodied carbon associated with new flooring production. Ecocel cellulose insulation is sustainable because it is locally produced in Cork from recycled newspaper, reducing waste, embodied carbon, and transportation emissions. Using a traditional window maker, Hunter Joinery from Tipperary, is sustainable because it supports local craftsmanship, reduces transport emissions, preserves heritage skills, and ensures the windows are repaira-ble and compatible with the historic fabric of a 500-year-old home. Gutex Thermoroom made from FSC-certified wood fibres vapour-permeable, fully recyclable, and produced using low-energy processes from by-products of the timber industry.