- New build

- Posted

Timber & Straw passive house is a world first

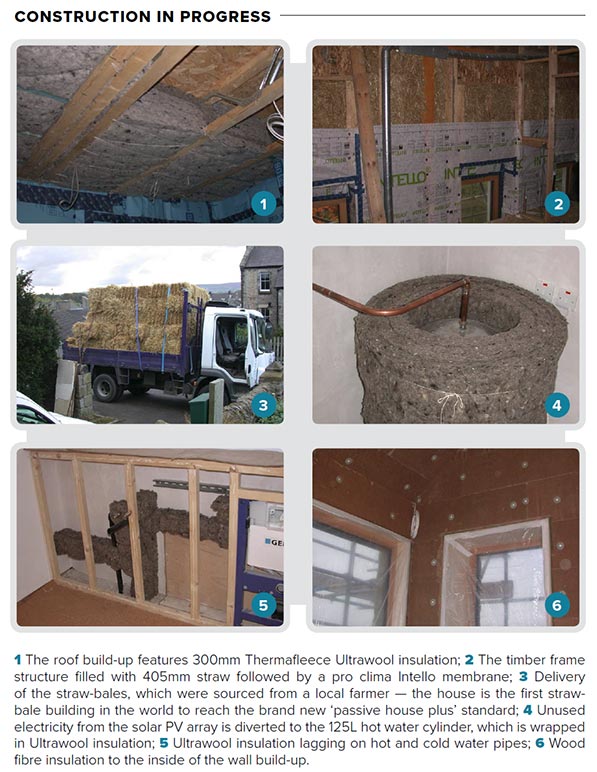

Built with a timber frame insulated with straw-bale, and featuring an extensive suite of ecological and recycled materials, this stunning North Yorkshire home also produces more energy than it consumes, making it the first straw-bale building in the world to reach the brand new ‘passive house plus’ standard.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Zero annual heating costs - or estimated £170 per year when leftover wood from build runs out.

Building type: Three-storey 145 sqm timber frame & straw-bale house

Completed: January 2017

Location: Leyburn, North Yorkshire

Build method: Cavity wall

EPC: A

Standard: Certified passive house plus

Electricity bills: £32 per winter quarter (January-March 2017)

Behind the construction of the straw-bale Leyburn passive house in North Yorkshire lies a long saga with many twists and turns. For the two owners, Ruth Barnett and Peter Richardson, it took personal sacrifice and determination to overcome fierce local opposition in order to build their dream home. But, after two planning refusals and a defeated appeal, the story ended in triumph when the redesigned house achieved certification to the new ‘passive house plus’ standard, which recognises the on-site production of renewable energy as well as the energy efficiency of the building.

The Leyburn passive house is unlike any other home in the Yorkshire Dales. The design is modern, but the cladding in local stone means that it blends in well with its surroundings, and there are lovely views over the hills from the slightly elevated position on the outskirts of the small market town. “There was a lot of antagonism and petitions from local people and it took three years to get it through planning,” says architect Adam Clark, of Halliday Clark Architects. “But we kept dusting ourselves down and took the suggestions of the planning team on board and tried again. Eventually it got through.”

Clark said that opposition to this type of modern design was common. “We get it a lot all over the country because our schemes tend not to be traditional in design,” he said.

“There are photovoltaic panels (PVs) on the roof and zinc cladding, creating a different palette of materials from other houses in the area, yet we have introduced stone cladding that has been sourced locally.”

Nevertheless, Ruth Barnett stresses that there was some support for the project locally too, and that many who initially objected have now changed their minds. “People come round at weekends to see the house and nearly all have a very positive reaction,” she says. “The stone cladding means it fits in better than a lot of the red brick houses in the area. There were also misunderstandings. Some locals were objecting to pictures they’d seen of the architect’s white model, but we never wanted to build a white piece of cardboard.”

This article was originally published in issue 23 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Barnett has always been interested in green architecture and modern design. A chartered surveyor by profession, she has a master’s degree in building conservation. Her dream of constructing an ecological house began 15 years ago when she read Barbara Jones’s book ‘Building with Straw Bales’, which fired her imagination. Then, a few years later, she read Will Anderson’s ‘Diary of an Eco-Builder’, which inspired her even more. Her partner, Peter Richardson, is a graphic designer and shares her passion for green design. They set about trying to find a plot that would accommodate a straw-bale house.

The pair found the site they wanted in Leyburn several years ago, but that was just their beginning of the struggle.

Explained

The ‘passive house plus’ standard is a new certification category designed to recognise the production of onsite renewable energy by passive buildings. It requires a minimum of 60k kWh/m2/yr of renewable energy generation, along with a maximum renewable primary (PER) energy demand of 45 kWh/m2/yr. PER is a new energy factor developed by the Passive House Institute designed for a future where electricity grids are powered entirely by renewables. It is designed to replace traditional primary energy demand in the long term. In this case, a higher PER demand, 56 kWh/m2/yr, was allowed because the dwelling produces much more (83 kWh/m2/yr) than the renewable energy generation target.

The even more advanced ‘passive house premium’ standard requires generation of 120 kWh/m2/yr and a maximum PER of 30 kWh/m2/yr. Meanwhile under this new system, the traditional passive house standard is rebranded as ‘passive house classic’, and has a max PER of 60 kWh/m2/yr, with no renewable generation required.

This new classification system is operational alongside the traditional passive house standard, with its maximum primary energy demand of 120 kWh/m2/yr, and no requirement for renewable energy production. The targets for space heating demand (15 kWh/m2/yr) and heat load (10 W/m2) remain the same under both certification systems.

The plot was in the Quarry Hills Conservation Area, which comprises a former Victorian workhouse and infirmary. The latter was converted into a pair of semi-detached houses nearly 30 years earlier. Barnett and Richardson bought one of these dwellings, which they now rent out, along with their site because the owners would not sell the plot alone. And although the site had been earmarked for development, and there had been two previous planning applications, nothing had been built yet.

Having sold their old home near Masham, they moved to Leyburn and commissioned Adam Clark to design a straw-bale house to level six of the Code for Sustainable Homes, the highest achievable rating.

Unfortunately, resistance to the design was intense. Richmondshire District Council, the Civic Society and the Town Council all opposed the development. “They were concerned that the initial design projected too far forward from the existing building, and wasn’t simple enough in terms of its composition to fit in with the surrounding houses in the conservation area,” says Clark.

At this early stage, there was no intention to build a passive house. But that all changed in March 2015 when Barnett approached Thomas Froehlich, a German structural engineer based in Scotland, for help in achieving code six status. Froehlich is the managing director of Ecowin, who sell Austrian-made Gaulhofer windows, but he is also a passive house consultant and suggested building to the standard. Ruth and Peter were excited by the idea and agreed it was the best way forward, and decided to aim for the passive house standard instead of code level six.

“But there were some difficult conditions to overcome to make it a passive house,” says Froehlich. “Firstly, it’s in a conservation area, which imposes restrictions. Secondly, it was not designed as a passive house and any alterations had to be made within planning limits using PHPP [the passive house design software], which was quite an exercise and we got through it by the skin of our teeth.”

And while passive buildings should ideally be as compact as possible to minimise the surface area for heat loss, this one was not, with a form factor (the ratio of the total surface area of the thermal envelope to the treated floor area) of 3.4, whereas 3.0 or under is ideal for meeting the passive house standard. The house’s thermal envelope is smaller than it appears. Outside of the treated floor area of 145 sqm – a relatively modest size for an architectural self-build – a garage and rooftop terrace eat into the footprint of the ground floor and second floor respectively.

Froehlich worked with Adam Clark to make sure the design could meet the passive house standard. Barnett and Richardson were committed to using natural materials wherever possible. The project used recycled concrete aggregate in its foundations and no cement-based products above ground. The interior was lined in lime plaster with a breathable Lakeland paint finish. “It’s very unusual to create a hybrid like this with all natural materials,” says Froehlich. “We weren’t even allowed foam around the windows.”

Froehlich made regular site visits and carried out the ‘toolbox talk’ on the passive house standard for the trades on site. He says, “When we first carried out a pressure test, the airtightness reading was 1.6, but because of the size and shape of the house we had to get it down to 0.3. It’s difficult with a hybrid structure, as you have to figure out how the render and the plaster will fit on the straw-bale. It took a few weeks but we managed it in the end due to the lime render and the airtightness.”

Though Adam Clark is enthusiastic about building with straw-bale, he is less fond of using the material for the load bearing structure. “You can use it that way, but it restricts your construction sequence, so we used the bales as insulation rather than as a structural element. I developed a technique of using TJI beams made from softwood and OSB. We created deep wall structures with structural bays that the bales could slot into.”

“The straw-bales were sourced from a local farmer. With regard to longevity, they are installed within a double membrane structure,” he says. “The external membrane prevents water ingress from the external environment, and the intelligent membrane to the inside face of the bales enables moisture to pass out of the bale if needed, but prevents moisture within the building passing into the bale.”

Renewable energy was obviously essential for achieving the passive house plus standard, which was introduced in 2015 along with the ‘passive house premium’ standard to recognise the production of renewable energy on-site (see explainer). The roof of the house features a 5.8kW array of Trienergia solar photovoltaic panels — each of the 29 panels has an output of 200W. The planning inspector stipulated that the PV array must cover the entire roof in order to achieve a uniform appearance, and Barnett spent a fair amount of time trying to find a PV product that could meet this demand and fit together to neatly cover the entire roof.

But Barnett took a hands-on approach during the build, and was happy to work on sourcing products herself, and in supervising on-site. “It was very much a self-build as the client hunted down materials and ran the scheme on site,” says Adam Clark. “Ruth and Peter are passionate and adamant about what they want. They are also knowledgeable and monitored everything well, so the need for a day to day involvement on site was not required.”

Barnett managed to source some of the products she needed from an eco-building supplier, Womersley’s Associates in West Yorkshire. But tracking down other components, such as the foamed glass products used to prevent thermal bridging below the ground floor was more challenging.

“The build began in May 2015 and the daily involvement was intense,” Barnett says. “There were a lot of people to satisfy. We had to source materials that were compatible with passive house rules, but also planning and building regulations, as well as the engineer’s stipulations.”

(above) Handing over the certificate for reaching the new passive house plus standard, pictured are (l-r) Ruth Barnett, Ecowin MD Thomas Froehlich, Peter Richardson, and Adam Clark of Halliday Clark Architects./em>

The couple moved into the house in January of this year, and since then Barnett has emailed Passive House Plus a couple of times with updates on how the house is performing.

“We are finding the external venetian blinds extremely effective in controlling overheating and have used them on numerous occasions,” she says. “We prefer them to fixed shading due to the flexibility they offer — we can decide when to block out the sun rather than having it decided for us.”

She also told us that the first quarterly electricity bill of 2017 came to just £32, with the Immersun controller for the solar PV system efficiently diverting excess generation to the hot water tank, meaning that as of mid-June, they had not needed to use the electricity grid to heat water at all. There is only one standalone stove, which burns wood leftover from the build and from trees taken down during site works, and three 70W electric towel rails.

As a result of working on the project, local tradespeople have now developed a specialism in passive house construction, which they can now take onto other builds. Meanwhile Thomas Froehlich and Adam Clark have since worked on two other passive house projects together – one in Ripon, North Yorkshire, and the other in Hawksworth, near Leeds.

Though the impetus to create a passive house came from Thomas Froehlich, he initially had doubts about building with straw-bale. But the success of the Leyburn house has transformed his view.

“This house converted me and if I built a passive house myself from scratch I would now do it with straw-bale. Most houses built in straw-bale are standard boxes, but this one isn’t and it proves what can be done with it. We were happy to achieve passive house status, and at the end of the day to get the passive house plus standard was the icing on the cake.”

Selected project details

Clients: Ruth Barnett & Peter Richardson

Architect: Halliday Clark

Structural design: Buro Happold

Electrical contractor: Gregg Electrical

Airtightness testing & SAP assessment: Award Energy Consultants

Misc. green building materials, sheep’s wool, foamed glass fill: Womersley’s Ltd

Misc. green building materials: MKM Building Supplies

Airtightness products & MVHR: Green Building Store

Windows, doors & venetian blinds: Ecowin

Roof window: Fakro, via MKM Building Supplies

Wood burning stove: The Stove Gallery

Solar PV: Gregg Electrical

Rainwater harvesting system: Rainwater Harvesting Ltd

Water conserving fittings & towel rails: Ripon Interiors

Reclaimed maple: Heritage Stone

Natural paint: Lakeland Paint

Cork underlay: Siesta

Kitchen units with recycled content: Milestone Design

In detail

Building type: 145 sqm treated floor area, detached three-storey timber frame house with straw-bale infill.

Location: Leyburn, North Yorkshire

Completion date: January 2017

Budget: Confidential

Passive house certification: Passive house plus certified

Energy bill: £170 per year for space heating, not including hot water (calculated using space heating demand from PHPP and average cost of wood logs as published by www.confusedaboutenergy.co.uk. In practice the house is heated with free waste wood leftover from construction/site works). Quarterly electricity bill of £32 for March to May, including VAT & standing charges, not incl feed-in-tarriff.

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 13 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 56 kWh/m2/yr [aka primary energy renewable or ‘PER’ demand]

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 3.41

Overheating (PHPP): 2% (of time indoor temp above 25C Environmental assessment method: None Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.30 ACH

Energy performance certificate (EPC): A 103

Thermal bridging: TeploTie low thermal conductivity cavity wall ties, Foamglas blocks, fibreboard waist at floor/wall junctions, thermally broken window frames, insulated reveals. Calculated Y-value: 0.019 W/m2K.

Ground floor: 1.4m strip concrete foundations with recycled aggregate. 500mm Foamit crushed glass, followed above by 50mm Foamglas slab; 250mm Limecrete with glass fibres; 100mm Thermafleece Ultrawool, finished above with reclaimed maple flooring. U-value: 0.082 W/m2K.

Walls: Lime render externally on 40mm fibreboard, followed inside by ventilated cavity, pro clima DB+ breathable membrane, timber frame filled with 405mm straw; pro clima Intello membrane; 60mm fibreboard; 20mm lime plaster internally. U-value: 0.087 W/m2K.

Roof: Solar PV array on liner tray system to south facade and natural slate to the north, followed inside by ventilated cavity, Nilvent breathable roofing felt, followed inside by 18mm OSB, 300mm Thermafleece Ultrawool insulation, 18mm ply, pro clima Intello membrane, 60mm fibreboard, 20mm lime plaster. U-Value: 0.092 W/m2K.

Windows: Gaulhofer Fusionline 108 triple glazed aluminium-clad larch windows, with argon filling and an overall U-value of 0.72 W/m2K.

Roof window: 5 x Fakro FTT-U6 triple glazed roof window with EHV-AT thermal flashing and overall U-value of 0.8 W/m2K. Heating system: Burley Springdale 3KW wood burner with 88.9% efficiency, 3 JSS Cinder x 70W electric towel rails. Immersun diverting otherwise unused electricity from solar PV array to the 125L hot water cylinder, before sending the remaining excess electricity to the grid.

Ventilation: Paul Novus 300 MVHR. PHI certified heat recovery efficiency rate of 94.4%.

Electricity: 29 x 200W Trienergia solar PV panels totalling 5.8kW, generating 83 kWh/m2.

Green materials: Reclaimed limestone, straw-bales, concrete with recycled aggregate, lime render and plaster, limecrete, wood fibreboard insulation, recycled foamed glass, all timber FSC or PEFC certified, reclaimed floorboards, recycled rubber flooring, cork underlay, sheep’s wool, cellulose and earthwool insulation, low flow taps, low flush WCs, rainwater harvesting, natural paints and oils, recycled plastic drainage products, recycled paper airtightness membrane, recycled plasterboard, recycled aluminium blinds, kitchen units including carcase from recycled particleboard, LED lighting.

Image gallery

-

Leyburn 08

Leyburn 08

Leyburn 08

Leyburn 08

-

Leyburn 01

Leyburn 01

Leyburn 01

Leyburn 01

-

Leyburn 02

Leyburn 02

Leyburn 02

Leyburn 02

-

Leyburn 03

Leyburn 03

Leyburn 03

Leyburn 03

-

Leyburn 04

Leyburn 04

Leyburn 04

Leyburn 04

-

Leyburn 05

Leyburn 05

Leyburn 05

Leyburn 05

-

Leyburn 06

Leyburn 06

Leyburn 06

Leyburn 06

-

Leyburn 07

Leyburn 07

Leyburn 07

Leyburn 07

https://mail.passive.ie/magazine/new-build/timber-straw-passive-house-is-a-world-first#sigProId361c285d62

View the original digital version of this article

- Issue 22

- timber frame

- Passive house certification

- space heating

- Cavity Wall

- straw bale

- passive house plus standard

- saint gobain